As principal investigator for the REVASCAT and DAWN trials and having leadership roles in the SWIFT PRIME and ESCAPE trials, Tudor Jovin (University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, USA) has been heavily involved in the development of the field of stroke treatment for many years. In this interview with NeuroNews, he discusses the development of his career, the urgent updates that need to be made in the stroke treatment strategy and gives his advice for young interventional neurologists.

As principal investigator for the REVASCAT and DAWN trials and having leadership roles in the SWIFT PRIME and ESCAPE trials, Tudor Jovin (University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, USA) has been heavily involved in the development of the field of stroke treatment for many years. In this interview with NeuroNews, he discusses the development of his career, the urgent updates that need to be made in the stroke treatment strategy and gives his advice for young interventional neurologists.

What drew you to medicine and interventional neurology in particular?

I grew up in a family of physicians. Both of my parents were physicians and my paternal grandfather was also a physician. I am the third generation physician in my family so it was very natural for me growing up—I never considered doing anything other than medicine.

As far as interventional neurology, this field was non-existent and it opened just as I entered medicine. What attracted me to stroke as a sub-specialty of neurology, was its overlap with internal medicine, which was my first love. At the time I started my neurological residency in 1997, there was great enthusiasm within the vascular neurology community generated by the recent publication of the landmark NINDS intravenous t-PA trial, which really marked a new era in acute stroke treatment; an era of aggressive attitude of vascular neurologists towards acute stroke treatment that accepted relatively high risks in order to reap the significantly higher rewards associated with this treatment. Back then, neurology was largely a diagnostic specialty, and was derided as such by other medical specialties—people would tell me “this is the diagnose and adios specialty”. It is a beautiful intellectual exercise in establishing the diagnosis but you cannot do anything about the condition you diagnosed. The NINDS trial, by showing benefit of iv t-PA in acute stroke has proven to be among the first of many efficacious interventions in neurology and has paved the way for a large variety of aggressive treatments for neurological conditions that have emerged in our field in the last 20 years since its publication. On the other hand, it was evident from being a resident in a busy hospital taking care of stroke patients that, while iv t-PA was a ground breaking advancement in acute stroke therapy, it was far from being the answer for all stroke patients as only a few patients met treatment criteria and even when these criteria were met, a large proportion of patients with large vessel occlusions still had poor outcomes.

The passion that I developed for stroke and the strong interest in improving outcomes of this devastating condition drew me to interventional neurology.

Furthermore, during my residency I was inspired by two neurologists (Camillo Gomez and Adnan Qureshi) who were fully trained (by non-neurologists) and were actively practising neuro-endovascular procedures. This provided the motivation and belief that there is a way for neurologists to be part of this field.

Who were your career mentors and what have you learned from them?

The person who had the most influential role in my thinking and my overall approach to cerebrovascular patients, whether medical or procedural is the vascular neurosurgeon Howard Yonas. Back in the mid 90’s vascular neuroscience was being practiced in a silo-type setting by neurosurgery and neurology without much interaction between these two specialities. However, it was Dr Yonas’ vision to create an integrated vascular neuroscience entity at the University of Pittsburgh where vascular neurologists, neurosurgeons and neuroradiologists were approaching neurovascular disease from a collaborative, multidisciplinary perspective and understood that each speciality truly has something to bring to the table, a concept I found to be really innovative. So even though I was a vascular neurology fellow coming from a neurology background, I had the privilege to train under him at the University of Pittsburgh. Back then he was one of the few, if not the only, neurosurgeons with a real passion for ischaemic cerebrovascular disease and specifically acute stroke. Furthermore, Dr Yonas had a physiological approach to patient care taking into account the pathophysiology of ischaemic disease of each individual stroke patient. That really opened my eyes to the world of ischaemic disease diagnosis and management. Another mentor who has had a decisive influence in my career is also a neurosurgeon, Dr Michael Horowitz. He is a type of person who totally thinks “outside the box”, which partly explains why he was not only willing to train me (a neurologist!!!) in neuro-endovascular techniques but fought the battle to make it happen by overcoming a lot resistance to this concept from certain stakeholders within our institution. There are other neurologists, neurosurgeons and neuro-radiologists under whom I trained who had important influences on my career and to whom I am extremely grateful.

Which innovations in neuroradiology have shaped your career?

Because my passion has always been acute stroke interventions, it is natural that a related procedure shaped my career the most. On top of the list I would put embolectomy. With all its limitations, the Merci device which proved the concept that you can actually go in, grab the clot and take it out of the body rather than using medication to dissolve it has been a decisive innovation for my career. These early iterations of mechanical embolectomy (including stents) were far from perfect and we have come a long way since, but they provided a valuable proof of concept which I used and tried to help develop to the best of my abilities, which has had a highly influential role in my career.

What has been the biggest disappointment—ie. something you thought would be practice-changing but was not?

The biggest disappointment but luckily something that we all have overcome by now was the publication in 2013 in the New England Journal of Medicine of three negative trials related to acute stroke intervention, particularly IMS III, which was a trial I had put a lot of passion into. Our centre had been the second highest enroller and I was actively involved in the trial not only at UPMC but also at trial leadership level. I believed passionately that we would show benefit with this approach and was very disappointed to see that the trial was stopped for futility after two-thirds of the patients had been enrolled. The other disappointment, which is still there and which I believe we will eventually overcome, are the negative results that emerged from two randomised trials of intracranial stenting for symptomatic disease. I am convinced that just like in the case with acute stroke interventions, these two trials are not the definitive answer to a disease that continues to portend a poor prognosis in certain subgroup of patients despite optimal medical therapy and that improved patient selection, improved technology and improved overall operator skills will result in positive trials that will make intracranial stenting the standard of care in certain circumstances.

With recent developments in the field, the face of stroke treatment is changing rapidly. What do you think are the most important changes that need to be made in line with this?

Short- and mid-term, the most important update is to make the infrastructure in terms of patient delivery to endovascular centres catch up with the enormous impact that embolectomy was found to have on patient outcomes. In 2015, based on five randomised trials, we showed a crushing benefit of endovascular therapy in acute stroke due to large vessel occlusion. Even though the treatment effects seen with this intervention are higher than those seen in percutaneous intervention for STEMI, large vessel occlusion stroke (LVO) treatment infrastructure lags behind cardiology by leaps and bounds. That means that we need to improve our ways of detecting the disease by raising awareness that stroke is treatable in a time dependent fashion and making patients seek urgent medical attention in massively larger numbers than currently achieved. We also need to improve pre-hospital delivery of care and ensure that the right stroke patient gets to the right hospital. Currently, we still operate within antiquated systems that send LVO patients to non-endovascular centres as a first destination. We know that the benefit of this procedure is exquisitely time-sensitive and currently we waste too much precious time with inadequate patient triage as LVO patients do not by-pass non-endovascular capable hospitals instead of going directly to a hospital capable of offering thrombectomy. These patient delivery paradigms need to change. We need to improve our intra-hospital systems of care processes to mirror the ones that are in place in the coronary area where patients routinely get to the cath lab table within 30 minutes from hospital arrival. At all phases—first medical contact, pre-hospital and intra-hospital—we need to improve the systems of care to better deliver this treatment so that more patients can be treated with better outcomes than currently achieved.

There are other priorities such as better understanding the role advanced imaging plays in patient selection and whether we really need to utilise as much imaging as we currently do. By introducing delays in reperfusion or by excluding patients who may still benefit, imaging could represent a barrier to treating more patients with better outcomes. Another important priority is to understand if there are adjunctive therapies that can make this treatment deliver better results when we combine, for instance, neuroprotection with reperfusion or use different adjunctive methods that would enhance the effect of thrombectomy.

What are the biggest developments you hope to see in the field of interventional neurology in the coming five years?

I hope to see a massive increase in the number of patients treated with embolectomy for stroke. I hope to see carotid stenting established as an equal alternative to endarterectomy and not as, unjustly labelled today, as second choice. In addition I hope to see second generation trials in intracranial stenting for symptomatic atherosclerotic disease that are positive. Further, we need to expand our horizons and start exploring approaches for conditions outside of what we currently treat.

What are the most important trial results that you are awaiting in 2017?

I may be seen as a bit biased but I have the privilege to co-lead the DAWN trial, which is a randomised mechanical embolectomy trial in patients with anterior circulation LVO stroke in the 6–24 hour time window. The opportunity to end the trial due to efficacy will exist at pre-planned interim analyses during 2017 if the treatment is efficacious enough. Of course, I do not know if that is going to be the case but I hope there will be sufficient benefit to allow this trial to be terminated and presented/published in 2017. If that is the case, I believe it will be a very important milestone in providing state-of-the-art evidence that this treatment is beneficial beyond the six-hour time window in selected patients with LVO stroke. We should not forget that outside of the USA, Canada and Europe, in most parts of the world, patients do not arrive at a hospital (much less endovascular capable one) within six hours of stroke onset, due to poorly developed systems of stroke care. And therefore, by establishing the benefit of embolectomy in the beyond-six-hour time window a positive trial would have significant repercussions on utilisation rates for embolectomy especially in those areas of the world where the systems for delivery of stroke patients are underdeveloped.

What advice do you hope your mentees and students will always follow?

Throughout my career I have trained many aspiring neuro-interventionalists of different basic specialities. This is one of the most professionally satisfying aspects of my work. With regards to neurologists training in neuro-interventions my concern is that some people are being trained based on the philosophy that they must forget their clinical background and dedicate themselves solely to interventions. I think that is a big mistake. What we emphasise to fellows whose background is neurology, is to cherish their neurology background and make use of it as much as possible in their practise. I tell them they have to “continue being doctors not only plumbers”. This is essential because this field will increasingly be dominated by clinicians. So that is one big piece of advice to our neurology mentees—never forget that you are a clinician and that you are a neurologist; it is your strength and your asset in the field.

The other one is very simple; just keep the best interest of your patient in mind and be prepared to take risks if you think they are worth it. This field is unforgiving in terms of its potential for devastating complications and every time you have one (because if you are in this field long enough you will are sure to have them) the single most important question you will ask yourself is “was this procedure justified?”

What is your most memorable case?

There are several cases that have stuck to my mind, but the most memorable one is the story of a gentleman in his late fifties who was admitted in a coma with a basilar artery occlusion. We did not have much information about his background but we found out immediately after the case that he had a really bad heart and was on the transplant list for a heart transplant. We were sceptical about his outcome given his terminal heart condition. But, the following day while he was still intubated he seemed to have a normal neurological exam. In the morning I got a call from the heart transplant surgeon telling me that by coincidence a heart became available for this gentleman and he asked me if I saw any reasons why he should not undergo the transplant especially in terms of his neurological outcome. In view of his significant clinical improvement, I said “no, no objections, go ahead. Let’s give him a chance”. And, lo and behold, this man underwent treatment for a basilar occlusion followed by a heart transplant within 24 hours. That was about 10 years ago, and he is still alive today and doing very well, at home fully independent with no neurological sequelae.

What are your interests and hobbies outside of medicine?

I have a very active social life. I love to travel and outside of work I do travel a lot with my family and friends. I have a lot of old friends from high school with whom I am in regular contact and I am typically in charge of organising our annual or twice yearly get-togethers in various parts of the world which at times can be quite a complex undertaking. I love to ski. On a day-to-day basis I read a lot (mainly non-fiction, politics, history, travel), watch movies, follow religiously the English Premier League Soccer, the Spanish La Liga and the Champions League and enjoy learning about wines from all the regions of the world through reading and tasting with my friends and colleagues with whom I regularly go out. Between work and spending time with my family (wife and three teenage daughters) there is not much time left.

Fact file

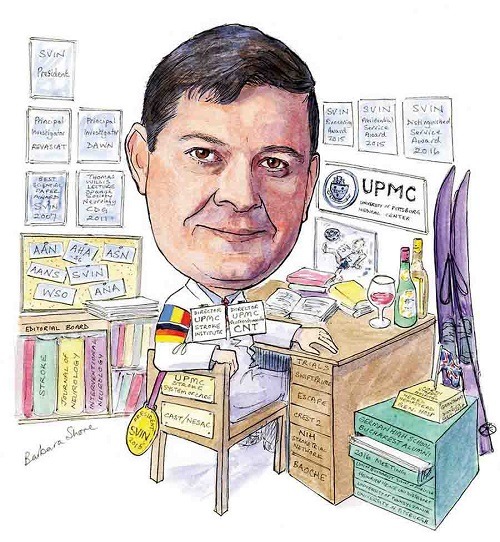

Current position

Director, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) Stroke Institute; division chief, Vascular Neurology; director, UPMC Center for Neuroendovascular Therapy; chair, UPMC Stroke Systems of Care; and professor of Neurology and Neurosurgery at UPMC.

Professional appointments and positions (selected)

- 2004–present Attending interventional neurologist, UPMC, Departments of Neurology and Neurosurgery

- 2005–2010 Director, Vascular Neurology Fellowship Program, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Neurology

- 2006–2012 Director, Neuroendovascular Fellowship Program, University of Pittsburgh of Medicine, Department of Neurosurgery

- 2010–present Director, UPMC Stroke Institute, Division Chief, Vascular Neurology, UPMC, Department of Neurology

- 2013–present Director, UPMC Center for Neuroendovascular Therapy, UPMC, Departments of Neurology and Neurosurgery

- 2015–present Chair, UPMC Stroke Systems of Care

Career highlights

- Principal investigator of REVASCAT

- Principal investigator of DAWN

- Leadership roles: SWIFT PRIME, ESCAPE

- Professor of Neurology and Neurosurgery (March 2016)

- Society of Vascular and Interventional Neurology (SVIN) president (2014–2015)

- SVIN Distinguished Service Award (2016)