The opening day of the 2023 International Stroke Conference (ISC; 8–10 February, Dallas, USA) saw the presentation of findings from an animal-model study that assessed multiple promising neuroprotective agents—with one of these candidates, an intravenous, uric acid infusion, exceeding a prespecified efficacy boundary.

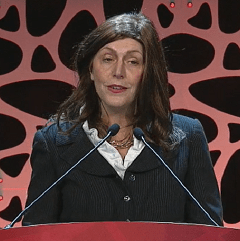

According to Lauren Sansing (Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, USA), who delivered these first-time data at ISC 2023, uric acid—proposed for testing by a team from the University of Iowa (Iowa City, USA)—now warrants further investigation to ascertain its utility in stroke care.

Sansing’s ISC presentation disclosed primary results from the Stroke Preclinical Assessment Network (SPAN), which was devised in an effort to address the lack of experimental rigour that currently impedes the translation of promising neuroprotective agents from animal models into clinical trials.

“In the past, a plethora of putative cerebroprotectants proceeded to clinical trials based on favourable preclinical assessment, only to fail in subsequent clinical trials of human stroke patients,” Sansing said.

With funding from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), SPAN adopted a clinical trial-esque design with a central coordinating centre and six independent laboratories that each tested six neuroprotective candidates. The candidates were:

- Fasudil, a rho-associated kinase (ROCK) inhibitor

- Remote ischaemic conditioning (RIC)

- Veliparib, a poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor

- Tocilizumab, a humanised interleukin-6 (IL-6) receptor antibody

- Uric acid, a potent free radical scavenger

- Fingolimod, a sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) analogue

Following randomisation, a total of 2,518 animals—including young mice and rats, ageing mice, mice with diet-induced obesity, and rats with spontaneous hypertension—constituted the intention-to-treat population in SPAN. Each laboratory then performed a ‘surgically induced stroke’, involving a standard transient middle cerebral artery (MCA) occlusion, in equal numbers of male and female animals. The animals subsequently received one of the neuroprotective treatments being studied or a placebo/sham.

For the study’s primary outcome, a corner test at day 28 post-treatment was used to assess the animals’ sensory and motor functions, while secondary outcomes included magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) lesion volumes and a grid-walk task.

The neuroprotective efficacy of each candidate was analysed via blinded-outcome assessments, and a multi-stage design through which—at 25%, 50%, 75% and 100% recruitment—said candidate’s progress would be halted if it demonstrated superiority (>50% treatment effect) or inferiority (<15% treatment effect).

Ultimately, 16mg/kg of uric acid given intravenously at the time of reperfusion was the only candidate that passed SPAN’s predetermined efficacy boundary and was therefore deemed successful.

In addition to this finding, Sansing highlighted that SPAN demonstrated the “highest possible rigour”, owing to treatments being concealed from surgeons, standard protocols, stratified randomisation, and blinded-outcome assessments, as well as maintaining “phenomenal” data quality, protocol adherence, throughput and timelines. She also concluded with a nod to SPAN 2.0 in which up to eight new interventions will be investigated under a similar study protocol.