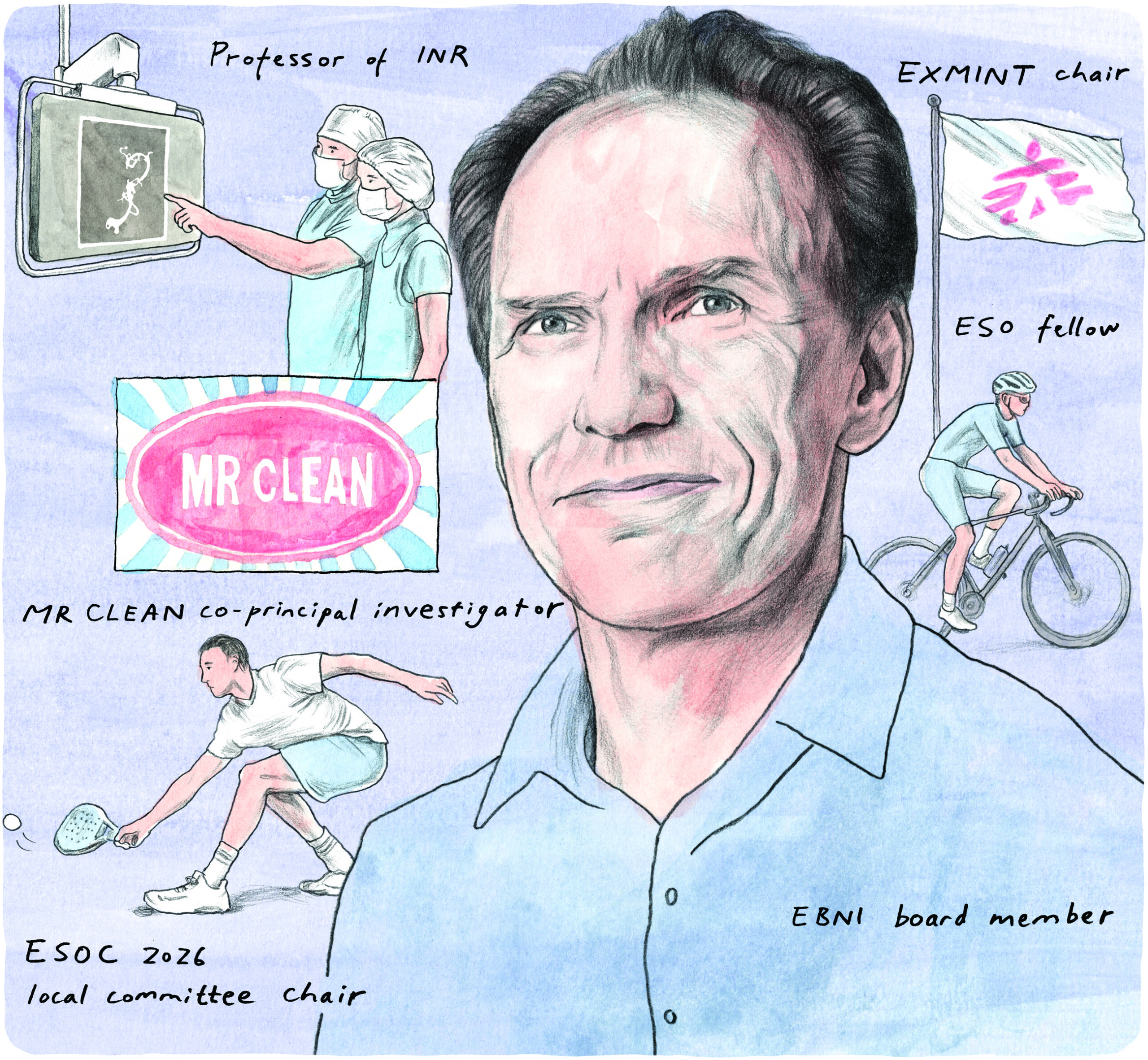

Following early-career flirtations with electrical engineering and then tropical medicine, Wim van Zwam (Maastricht, The Netherlands) eventually found his calling in interventional neuroradiology (INR) around the turn of the century. Many patients, physicians and researchers are likely very thankful that he did, owing to his significant contributions to the neurointerventional space over the past two decades—including as co-principal investigator (PI) of the MR CLEAN randomised controlled trial (RCT), chair for the European Stroke Course in Minimally Invasive Neurological Therapy (EXMINT), and a long-time advocate of improved global access to stroke treatments. Here, Van Zwam—an interventional radiologist and INR professor at Maastricht University Medical Center—sits down with NeuroNews to discuss his career to date, aspirations as local committee chair for next year’s European Stroke Organisation Conference (ESOC), unmet needs in the field of stroke care, and more.

What initially drew you to medicine, and the field of neuroradiology specifically

Well, to be honest, I wasn’t immediately drawn to medicine. I started studying electrical engineering but, after a little less than a year, I realised this was not what I wanted. Some of my former classmates had started with medicine and they suggested that I join them. In one of my first years studying medicine, I got interested in tropical medicine by a very active group called Working Group Medical Development Cooperation (WEMOS). So, I did the Dutch subspecialty in tropical medicine and started to work for Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders). After three years, having worked on three projects in Somalia, Laos and Sri Lanka, my wife and I decided to continue our lives back in The Netherlands. I applied for several different specialties, among them radiology. With my surgical background as part of the tropical medicine training, interventional radiology was the obvious choice—and, in Maastricht, where I did my training as an interventional radiologist, INR had just taken off. There was the perfect opportunity for me to enrol in this relatively new subspecialty in early 2000. I went for training in Tilburg, The Netherlands and later Essen, Germany, and attended Pierre Lasjaunias’ course in Thailand.

Who have your mentors been and how have they impacted your career?

In my early career, the head of surgery where I did my tropical training was Nomdo Bosma, the most humble and friendly—but still extremely skilful—surgeon I have ever worked with. Another mentor and example for me, even to this day, is my direct interventional radiology colleague Michiel de Haan. His high standard of professionalism is hard to achieve but, for all who work with him, it’s a goal to reach for. In INR, there are too many to mention, from Pierre Lasjaunias, Karel ter Brugge and Willem Jan van Rooij to René Chapot, Vincent Costalat and Christophe Cognard, and many more; they have all inspired me in a way, and still do. Finally, when I embarked on the stroke research journey, my MR CLEAN co-principal investigators, Diederik Dippel, Charles Majoie, Aad van der Lugt, Yvo Roos and Robert van Oostenbrugge showed me how collaboration and forgetting about egos could lead to great achievements. Thanks to them, I’m in this current position of having the opportunity to honour them.

What are you hoping to achieve as local committee chair for ESOC 2026?

First and foremost, my primary goal is to ensure ESOC 2026 in Maastricht delivers an outstanding scientific meeting—a platform where global experts can exchange knowledge on every facet of stroke care. Given the transformative advances in stroke treatment, and particularly the rise of mechanical thrombectomy, endovascular therapy for acute ischaemic stroke will be a central focus. ESOC 2026 aims to provide neurointerventionists with a comprehensive programme, including hands-on simulator training, and dedicated sessions on technical challenges, complications, and the latest scientific breakthroughs in the field. Beyond science, stroke advocacy remains a priority. Together with the ESO, World Stroke Organization (WSO), World Health Organization (WHO), and other partners, we will amplify efforts to elevate stroke on the global health agenda—especially in underserved regions—by engaging policymakers and stakeholders to improve access to treatment. Finally, sustainability will be a cornerstone of ESOC 2026. As healthcare professionals, we must lead by example in addressing climate change, which directly impacts stroke burden. We’ll promote eco-friendly practices, such as prioritising train travel and embracing cycling—the Dutch way—to demonstrate that sustainable conferences are achievable today.

Could you outline the significance of EXMINT and the main goals of the course?

The European Society of Minimally Invasive Neurological Therapy (ESMINT) has been and is the society for neurointerventionists. Traditionally, neurointerventionists focused on neurovascular diseases like aneurysms and arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) that were usually treated in a subacute, daytime setting. With the implementation of acute endovascular stroke treatment, not only did the number of treatments increase tremendously, but 24/7 coverage was also required. One option would have been to train many more ‘full’ neurointerventionists to cover these stroke treatments, with the downside being that these neurointerventionists would only be treating 10 aneurysms and one or two AVMs per year. The other option, adopted in many countries worldwide, was to train other physicians—interventional radiologists, neurologists or cardiologists—to perform mechanical thrombectomies without being trained as full neurointerventionists.

ESMINT recognised this need and started a theoretical course for stroke interventionists, named EXMINT, eight years ago. The course consists of an online module in November and a face-to-face module, including hands-on training, in February, followed by an online examination in May. Thanks to the huge efforts of course director Antonín Krajina, this has become extremely successful, and the number of participants is increasing year by year. Many of the participants travel from all over the world to Prague, Czechia to attend the course. Because the number of participants is becoming too big for proper hands-on training, and because many of the non-European participants come from Asia, we are currently exploring the idea of organising a parallel face-to-face module in Asia. This initiative aligns well with the previously mentioned stroke advocacy activities—when policymakers want to address the burden of disease from stroke, they need physicians who are able to perform stroke treatments.

How would you assess the legacy of the MR CLEAN study, as well as the ongoing research efforts of the CONTRAST consortium?

You may see the MR CLEAN study as just one of seven RCTs—alongside ESCAPE, EXTEND IA, PISTE, REVASCAT, SWIFT PRIME and THRACE—addressing the same question: does endovascular thrombectomy improve the lives of patients suffering from a large vessel occlusion stroke? However, due to the fact that MR CLEAN had the broadest inclusion criteria and was done in all Dutch centres performing thrombectomies at that time, it was not only the first RCT to reach its intended inclusions but it also immediately showed the wide applicability of this treatment. Had another study with stricter inclusion criteria performed in selected high-volume centres been the first to show the efficacy of thrombectomy, we would probably have implemented and expanded the treatment more slowly. Another positive effect of successful collaboration between different specialties and hospitals is that it may lead to larger consortia working together on new research projects. CONTRAST is the consortium that came out of MR CLEAN. Several studies have been done and are still being done under this umbrella, such as MR CLEAN-NO IV, -MED and -LATE, and the CASES study on tandem occlusions. New initiatives also include topics within haemorrhagic stroke. Collaboration with other research groups from Canada, Switzerland and China have opened doors to more extensive research projects with broader patient populations too. This may not be a legacy of MR CLEAN only, but MR CLEAN at least set an example, and many researchers worldwide wanted to know how stroke networks and research projects were organised in The Netherlands.

Besides stroke thrombectomy, what has been the most important development in the neurointerventional field during your career?

When I got involved in neurointerventions, the ISAT trial was still ongoing. The results of this trial had a tremendous impact on neurointerventional practices—all because of the development of the detachable coil. Later additions like balloons, stents, flow diverters and intrasaccular devices all improved the technique and expanded the possibilities for endovascular aneurysm treatment, but none changed practices as much as the detachable coil. And, as far as I know, none of these innovations have been investigated as thoroughly in a randomised trial as the detachable coil technique was in ISAT.

What is the most pressing unmet need in INR right now?

Stroke has become one of the most prominent causes of disability and, because many patients stay alive but remain severely disabled after stroke, the disease has a high burden for societies—not only in the developed world, but also in less developed countries, where healthcare systems have improved over the past few decades while the focus on stroke has lagged behind. We have also seen that, for these less developed or ‘newly developed’ countries, focusing on stroke management not only improves overall quality of life but is cost-saving in many ways as well. However, to address gaps in stroke management, resources and manpower are seriously needed. Resources must come from policymakers and insurance companies who pay for the care of stroke survivors. Manpower needs to be recruited from physicians working in various disciplines. As mentioned above, we try to address this gap by providing theoretical training for stroke interventions through the EXMINT course. For practical education, training centres and fellowships need to be created. This is currently one of the biggest challenges in our field.

Which research areas or innovations are likely to have the greatest impact on neurointerventional care over the next 5–10 years?

Personalised medicine—and the introduction of artificial intelligence (AI) tools to make this personalised medicine possible—will probably have a large impact on the way we execute our profession. We already see examples of personalised medicine in stroke prediction tools like MR PREDICTS, where combinations of clinical and imaging data are used as input variables for an AI algorithm to estimate the chances of certain outcomes. Physicians may use these chances to decide on treatment selection. Other choices like prehospital decisions based on availability of treatments, travel distances and patient characteristics, or treatment choices based on clot characteristics, can all be tailored by various AI tools using available data. We can see these AI tools entering our research field already and, with more data resulting from trials and registries, these tools will become increasingly accurate, opening up possibilities in patient and treatment selection that we couldn’t have dreamed of 10 years ago.

What advice would you give to people embarking on a career in interventional neuroradiology?

Keep an open mind for alternatives, new ideas and innovations. The neurointerventional field has, for many years, been the area of ‘expert opinions’; the relatively small number of patients affected by haemorrhagic neurovascular diseases and the high levels of skill needed to treat neurovascular diseases endovascularly did not leave many other ways to be trained in neurointerventions. As a result, skills and techniques developed by ‘the master’ were automatically adopted by the fellow. But, with currently available data from research—but also from various data sharing platforms—and the exchange of options via courses, congresses and online discussion groups, it has become possible to learn from many other ‘masters’. Moreover, achievements in ischaemic stroke research have shown us that, through cross-centre and cross-discipline collaborations, it is possible to incorporate evidence-based medicine within the neurointerventional world. Young fellows still need to be trained by experienced masters, but their sources of knowledge can be much broader now compared to when I started 25 years ago. So, use these sources and be open to implementing this knowledge in your practice.

What are your interests outside of the neurointerventional field?

My background is in tropical medicine, and my overall interest in global health still plays a significant role. The three years I worked for Médecins Sans Frontières were very important in shaping me as a person. I’m currently involved in stroke advocacy projects in the WSO’s Global Stroke Action Coalition, I hope to organise an EXMINT module in Asia, and I’m a regular teacher at the Stroke Winter School in Switzerland and Stroke Summer School in India. Most important outside of my profession is, of course, my family life. Spending holidays with my family in many different parts of the world has probably been the most rewarding activity over the past few decades. In my sparse free time, I like to ride my gravel bike—I go to work on my bike every day, anyway—and I recently started playing padel. Furthermore, I like to listen to alternative rock music and attend concerts; my current favourite band is Big Big Train.

Do you listen to rock music in the angio suite?

If it were my choice, I would! For awake patients, we usually leave it to their preference, or we select ‘middle-of-the-road’ radio station music in order to keep everybody at ease and satisfied. I’m afraid that my choice of alternative rock would chase some of our personnel out of the room.

If you had not chosen a career in medicine, what do you think you would be doing for living today?

Although I initially studied electrical engineering and still enjoy handling technical maintenance tasks at home, I don’t think I would have pursued a purely technical career long term. Instead, I likely would have ended up working for a non-governmental organisation (NGO) somewhere in the world, focusing on logistical and organisational tasks, eventually moving into politics or another socially impactful role.

FACT FILE

Current appointments:

- Professor of neurointerventional radiology, Maastricht University Medical Center (MUMC; Maastricht, The Netherlands)

- Interventional and forensic radiologist, MUMC

Education:

- 2004: International diploma in neurovascular diseases, MSc (Paris-Sud University, Paris, France)

- 2002: Radiology (MUMC)

- 1992: Tropical medicine (Royal Tropical Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands)

- 1989: Medical study, MD (Free University, Amsterdam, The Netherlands)

Honours (selected):

- Chair, EXMINT

- Fellow, ESO

- Member, European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Council on Stroke

- Member, European Board of Neurointervention (EBNI)

- Principal investigator for MACCA, MR CLEAN and MR CLEAN-LATE studies