Researchers have created nanoscale robots that could be used to manage bleeds in the brain caused by aneurysms, potentially enabling a more precise and relatively low-risk treatment approach.

A study published recently in the journal Small “points to a future where tiny robots could be remotely controlled to carry out complex tasks inside the human body” in a minimally invasive way, according to a team fronted by clinician researchers from the University of Edinburgh’s School of Engineering (Edinburgh, UK) and the Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (Shanghai, China). Such tasks include targeted drug delivery and organ repair.

“Nanorobots are set to open new frontiers in medicine, potentially allowing us to carry out surgical repairs with fewer risks than conventional treatments and target drugs with pinpoint accuracy in hard-to-reach parts of the body,” said Qi Zhou (University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK), who co-led the study. “Our study is an important step towards bringing these technologies closer to treating critical medical conditions in a clinical setting.”

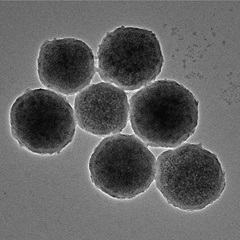

The research team engineered magnetic nanorobots about a twentieth of the size of a human red blood cell comprising blood-clotting drugs encased in a protective coating that are designed to melt at precise temperatures. In lab tests, several hundred billion of these bots were injected into an artery and then remotely guided as a ‘swarm’—using magnets and medical imaging—to the site of a brain aneurysm.

Magnetic sources outside the body then cause the robots to cluster together inside the aneurysm and be heated to their melting point, releasing a naturally occurring blood-clotting protein, which blocks the aneurysm to prevent or stem bleeding into the brain.

The international research team successfully tested their devices in model aneurysms in the lab and in a small number of rabbits. The researchers say that nanorobots show potential for transporting and releasing drug molecules to precise locations in the body without risk of leaking into the bloodstream—a key test of the technology’s safety and efficacy.

The researchers also believe the study could pave the way for further development towards trials in people.

Their advance could ultimately improve on current treatments for brain aneurysms, whereby doctors typically thread a tiny microcatheter tube along a patient’s blood vessels before using it to insert devices that either stem the aneurysmal blood flow or divert the bloodstream in the artery. The researchers posit that their new technique could decrease the risk that the body will reject implanted materials, and curb reliance on anti-blood-clotting drugs, which can cause bleeding and stomach problems.

In addition, this new method avoids the need for doctors to manually shape a microcatheter to navigate a complex network of small blood vessels in the brain in order to reach the aneurysm—which is described by the researchers as a “painstaking task” that may take hours during surgery.

Larger brain aneurysms—which can be particularly difficult to stem quickly and safely using metal coils or stents—could potentially be treated using the new technique too, the researchers believe.

The study recently published in Small was led by a team from the UK and China who have also developed nanorobots to remove blood clots, meaning they hold potential in the treatment of stroke.