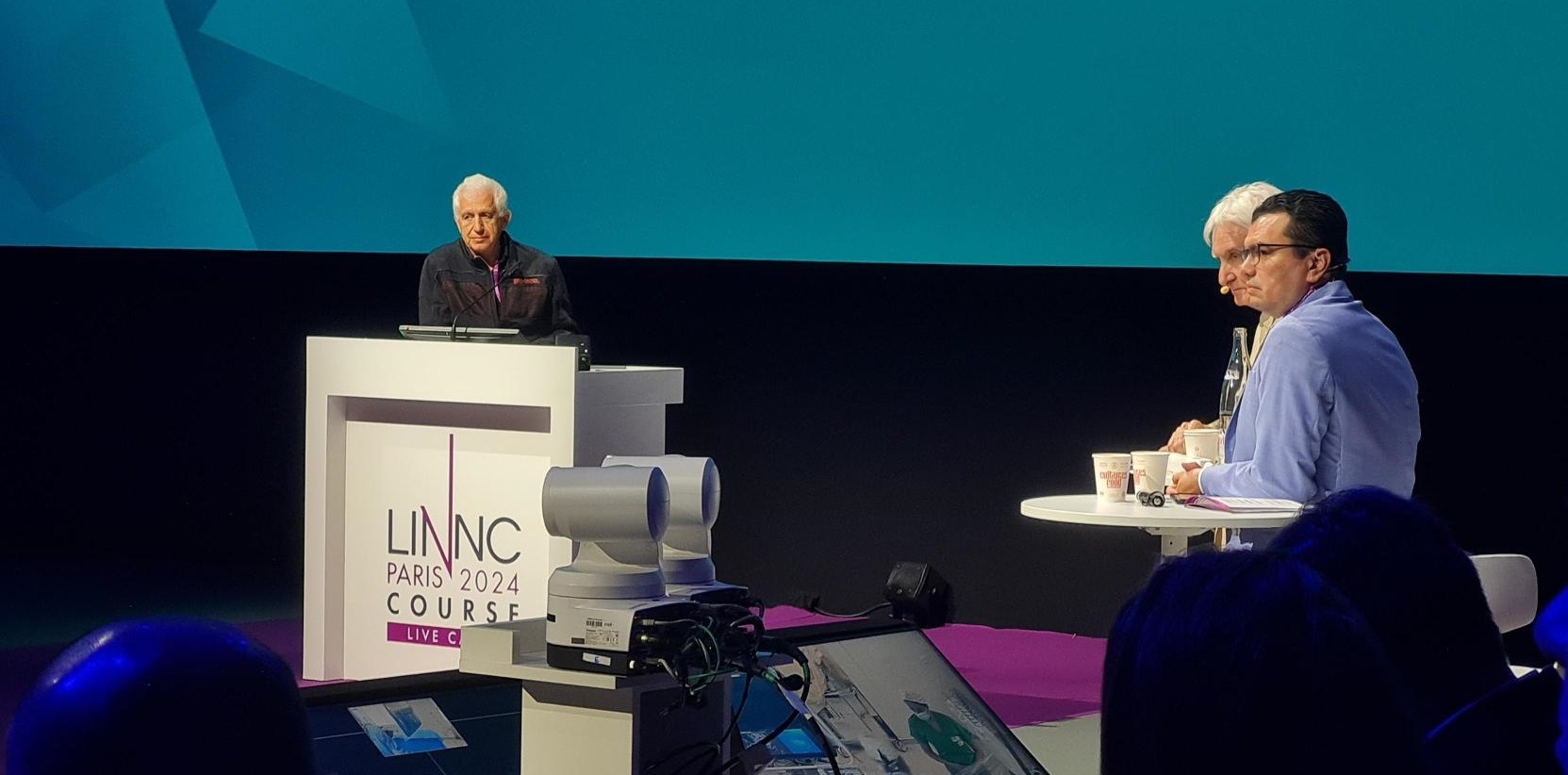

“I think complication discussion is one of the most important parts of our job,” said Edoardo Boccardi (Niguarda Hospital, Milan, Italy), prefacing his presentation of a neurointerventional case at LINNC Paris 2024 (3–5 June, Paris, France). As part of the meeting’s ‘Dark Side of INR [interventional neuroradiology]’ programme, Boccardi outlined lessons learned from a “terrible complication” encountered during the treatment of a dural arteriovenous fistula (dAVF).

The patient undergoing treatment in this case was a healthy 63-year-old woman who presented with a troubling and disabling bruit in her ear. Examination on imaging revealed that the patient had a sigmoid-transverse sinus dAVF with no drainage into the cerebral veins.

Boccardi and his colleagues elected a treatment indicated for such cases: embolisation of the fistula via an endovascular procedure. They placed a venous remodelling balloon (Copernic; Balt) in the sinus for protection and embolised the dAVF using an injectable liquid embolic agent (PHIL; Microvention/Terumo).

Walking the audience through the treatment, Boccardi reported a “very nice reduction of flow” when initially injecting the liquid embolic, also demonstrating “almost-complete occlusion” of the dAVF.

“You can see,” he said, referring to imaging recordings taken during the case itself, “there is more [of the liquid embolic] around the sinus, but the fistula is almost gone and the brain veins look okay. All is well. We inject a little more—I inject a little more—and, from here, we get to this image.”

At this stage, Boccardi outlined the root cause of the complication that would ultimately result in the failure of the case: he had unknowingly been injecting the liquid embolic into a vein, having mistaken it for an artery on imaging. Subsequent imaging revealed that the agent had been injected into and occluded the vein of Labbé, and the patient’s temporal veins.

“So, what do we do now?” Boccardi queried. “There’s probably not much we can do—we gave heparin, of course. We might have tried to take PHIL out; we have tried once before to take it away but it’s really difficult, so, we didn’t do it.”

He revealed a post-treatment computed tomography (CT) scan showing a “big haemorrhage” that got “much worse” over the next few hours, resulting in “blood all over the place, especially in the ventricles”.

“She does not wake up,” Boccardi noted, sombrely, displaying a series of scans depicting how the patient’s condition on imaging worsened over the following weeks, before reporting that she remained at a rehabilitation centre in a vegetative state at four months and died two years later.

“This is a terrible complication, and my mistake was that I took the filling of a vein for the filling of a meningeal [artery] feeder—I thought it was an artery when, in fact, it was a vein,” Boccardi continued. “Which vein was it? The inferior temporal vein, on the edge of the temporal lobe.”

The presenter then used multiple examples of imaging taken from other cases to demonstrate just how close this vein is to the artery he mistook it for—and, therefore, how difficult it is to distinguish between the two. Boccardi stated that they appear to be “in exactly the same place”, even when viewed from lateral or oblique imaging perspectives.

In addition to this error during the procedure, Boccardi highlighted multiple other potential mistakes that may have contributed to the failure of the case: the decision to treat the patient via embolisation in the first place; injecting “a little more” of the liquid embolic when the treatment appeared to be going well already; using PHIL rather than an alternative agent like Onyx (Medtronic) or Squid (Balt), small quantities of which are less likely to occlude a vessel; and not protecting the Labbé vein with a balloon.

Expanding on the last of these points, Boccardi asked rhetorically if it is “dangerous” to treat these types of fistulas with balloon protection. Here, he cited data spanning 325 intracranial dAVFs treated endovascularly at his centre from 2006 to 2017, revealing that 43 of these procedures utilised balloon protection and, of the 40 where a balloon was deployed in the sinus specifically, only one (2.5%) resulted in a fatal haemorrhagic complication—with that being the case he had just presented.

“So, the conclusion is that dAVF treatment with balloon protection may be dangerous, but usually isn’t,” Boccardi added.

“This is not just a bad case,” said LINNC course director Jacques Moret (Bicêtre Hospital, Le Kremlin-Bicêtre, France), putting forwarding another take-home message. “It is an incredible case for the understanding of [everything] that we are not looking at when we do the treatment, and what we don’t see before doing the treatment.”