While a recent survey found that a majority of those who responded had performed mini-incision carotid endarterectomy (CEA) at least once in their practice careers, most answered that they did not perform the surgery routinely.

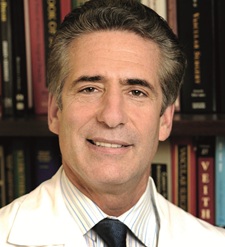

In the world of general surgery, no one would opt for a large abdominal incision if they could perform a mini-incision laparoscopic procedure, ponders Alan Dietzek (Jersey Shore University Medical Center, Neptune, USA). Yet, “in the vascular world”, he says, “for whatever reason, having a large neck incision is still acceptable versus having a small one”.

Dietzek was speaking to Vascular Specialist in the aftermath of a recent survey that showed more than 65% of those who responded had carried out a mini-incision CEA on at least one occasion and 19.2% always did so. Furthermore, respondents who performed the operation less frequently were significantly more likely to report that it provides less exposure and that patients are unconcerned about incision size.

The survey, sent to 1,110 Society for Clinical Vascular Surgery (SCVS) members, garnering a 13% response rate, sought to establish barriers to routine use of mini-incision CEA. The results were presented at the 2025 SCVS annual symposium (29 March–2 April, Austin, USA) by Keerthivasan Vengatesan (Danbury Hospital, Danbury, USA).

Dietzek says that among those barriers, as outlined by the survey, was “the fact that surgeons are afraid there won’t be enough exposure”.

More importantly, he continues, “if they have never done mini-incision carotid surgery, they are not likely to do it. Those who are coming out of training are likely to do the surgery if someone else in their practice is already doing the surgery. Or if they haven’t learned it in training, but if there are others in their practice that are doing mini-incision carotid surgery, there is a good chance that they will likely perform mini-incision carotid surgery”.

The survey laid out that only 31.5% of respondents were trained to perform mini-incision CEA prior to beginning practice, and that those surgeons were significantly more likely to have performed the operation in practice. Additionally, surgeons who always performed the surgery with patch angioplasty were significantly more likely to do so even in patients with higher-risk features such as high bifurcation, short or obese neck, and redo surgery, although this was not observed in those who always utilised shunts during mini-incision CEA, Dietzek and colleagues established.

Although the CEA patient population tends to be slightly older and less concerned with cosmetic outcomes, Dietzek considers, “I don’t think anybody would prefer to have a larger incision than a smaller incision unless they thought their outcomes would be worse”. To this end, Dietzek points to data in the literature showing outcomes after mini-incision CEA “are just as good as any other incision for carotid surgery”.

Therefore, Dietzek says, teaching fellows and residents how to do the operation is the most important factor in them then adopting it when they head out into practice.

“Having done this for more than 20 years, I would say that I can’t even recall having to extend the incision during an operation because I’ve had inadequate exposure,” Dietzek adds, explaining how the exposure—sometimes measuring as low as 4cm or less—is achieved by dividing the platysma muscle beyond the skin incision, enabled with the use of retraction. “It does occur but it’s so uncommon that it is not the kind of thing where you have to be fearful that you’re going to be boxed in when you are doing the operation in this manner. If you do have to extend the incision, that’s something you probably may have to do early on when you are first learning how to do it.”