This advertorial is sponsored by Acandis.

Following the recent approval and launch of the RESOLVE study evaluating the SiREX® Stent (Acandis) in the treatment of symptomatic lateral transverse sinus stenosis (TSS), Emmanuel Houdart (Lariboisière Hospital, Paris, France)—a leading expert on pulsatile tinnitus—discusses the condition and the potential benefits of a dedicated device in this space.

What is the role of transverse sinus stenosis in pulsatile tinnitus?

TSS is the leading cause of pulsatile tinnitus. However, since it is not the only one, it cannot be discussed without addressing the broader issue of pulsatile tinnitus as a whole. For example, in my personal series over the past eight years, approximately 1,600 patients were evaluated for pulsatile tinnitus and 32 different causes were identified.

Pulsatile tinnitus is a chronic symptom, sometimes highly debilitating or even leading to suicidal ideation, and remains too often under-recognised by the medical community. Why is this the case? Because most ear, nose and throat (ENT) specialists do not investigate the specific typology of tinnitus. They often refer to tinnitus without describing the nature of the sound perceived by the patient—in other words, they fail to use a qualifying adjective for the term.

The most common type of tinnitus is continuous tinnitus—the adjective ‘continuous’ does not refer to the temporal pattern of the tinnitus but, rather, whether it is constant or intermittent. This is typically a horizontal noise, most often a high-pitched whistling sound, with no identifiable cause or curative treatment. Since this type of tinnitus is the most prevalent, there is a tendency toward cognitive simplification, leading to the assumption that all tinnitus is continuous and therefore incurable. This is particularly detrimental to patients with pulsatile tinnitus, as pulsatile tinnitus is, in many cases, curable.

How is pulsatile tinnitus diagnosed?

Tinnitus is a perception and, therefore, its positive diagnosis relies entirely on the patient’s description. Pulsatile tinnitus is characterised by a sound that is synchronised with the patient’s heartbeat. Recognising it requires the clinician to reproduce or mimic a pulsatile sound, most often with a whooshing or blowing quality, to help the patient confirm the similarity.

How is the cause of pulsatile tinnitus identified?

Determining the aetiology of pulsatile tinnitus is a task for specialists, and requires the integration of clinical and radiological data. Physical examination is crucial, as imaging alone often does not lead to a definitive diagnosis. One essential component of the physical exam is the selective compression of the internal jugular vein and then the common carotid artery on the side of the tinnitus in order to assess whether the sound is interrupted. Based on the result of this manoeuvre, pulsatile tinnitus can be classified as: venous, if it disappears with jugular vein compression; arterial, if it disappears with common carotid artery compression; or neutral, if it persists despite both compressions.

Radiological assessment includes a dedicated brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan with three specific sequences: a large non-contrast 3D time-of-flight (3DTOF) sequence to detect arteriovenous fistulas, a high-resolution T2-weighted sequence focused on the internal auditory canals, and a contrast-enhanced T1-weighted magnetisation-prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE) sequence to visualise the venous sinuses. This MRI is complemented by a high-resolution computed tomography (CT) scan of the temporal bone.

How is pulsatile tinnitus due to TSS recognised?

The diagnostic criteria are those defined in the RESOLVE study. The tinnitus must, of course, be pulsatile. Clinically, it must be of venous type, meaning it should completely disappear with compression of the ipsilateral internal jugular vein.

On MRI—specifically the contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MPRAGE sequence—there must be a stenosis of both transverse sinuses, or of the ipsilateral transverse sinus if the contralateral sinus is aplastic. There should be no other identifiable cause of pulsatile tinnitus on imaging.

Finally, the stenosis must be associated with a trans-stenotic pressure gradient, the threshold value of which depends on whether or not a dehiscence of the sinus into the mastoid air cells is present on high-resolution temporal bone CT. In the absence of dehiscence, the pressure gradient must be at least 3mmHg under general anaesthesia.

What is your experience with TSS stenting?

The total series of TSS stenting procedures performed at Lariboisière Hospital includes 950 patients. The majority of cases have been treated over the past eight years, with a marked increase in patient referrals largely driven by social media exchanges between people suffering from pulsatile tinnitus and those who had already undergone successful treatment.

What stent do you currently use?

TSS stenting is currently performed using non-dedicated stents, most commonly carotid stents or intracranial stents like ACCLINO® flex plus (Acandis). At Lariboisière Hospital, we are currently using the Carotid Wallstent (Boston Scientific). This stent, however, has several limitations, including:

- Insufficient length—it is often not long enough to treat both the stenosis and a possible post-stenotic sinus dehiscence and, as a result, it is frequently necessary to overlap a second stent, which adds complexity to the procedure.

- High rigidity—its stiffness makes delivery more difficult and may cause postprocedural pain due to excessive dural stretching.

- Poor end finishing—the unfinished stent ends carry protruding struts that can potentially perforate cortical veins draining into the sinus, with the risk of causing the serious complication of acute subdural haematoma.

What would be the ideal characteristics of a stent dedicated to TSS?

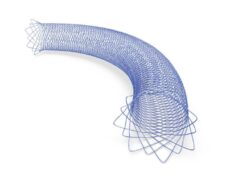

An ideal sinus stent should address the three main limitations observed with currently used devices. The SiREX Stent has the closest design to that of the Carotid Wallstent while improving on its drawbacks. It is self-expanding and recapturable, has been designed with closed, narrow cells to provide acoustic insulation in case of associated sinus dehiscence, and engineered with reduced radial force, and is trackable through a 0.052-inch lumen catheter. Importantly, its ends are atraumatically machined to minimise the risk of damaging cortical veins. And, being a braided stent, it likely conforms better to the morphology of the sinus than laser-cut stents with large cells.

Another option, the River stent (Serenity Medical), is a laser-cut, open-cell stent that also conforms well to the sinus anatomy. Its conical shape adapts to the variations in diameter along the sinus. However, it cannot be recaptured once deployed. It remains difficult to define in advance which stent design will prove superior—and clinical experience will ultimately determine which performs best.

What is the design of the RESOLVE study?

The RESOLVE study is a prospective, international, multicentre trial that will include 78 patients with pulsatile tinnitus caused by TSS. It is the first study on TSS stenting where the primary endpoint is the complete resolution of pulsatile tinnitus.

What are your expectations for the RESOLVE study?

The primary goal is to evaluate the safety and efficacy of this dedicated venous stent. The secondary goal is to prospectively demonstrate—across multiple centres, and using strict inclusion and exclusion criteria—that it is possible to cure pulsatile tinnitus associated with TSS.

What future do you envision for TSS stenting?

The future of sinus stenting will depend on the development of management strategies for pulsatile tinnitus, but it is certainly expected to grow significantly. In France alone, approximately four million people suffer from tinnitus, and 5% have pulsatile tinnitus, which corresponds to around 200,000 individuals.

How can their care be facilitated? The first prerequisite is raising awareness among the ENT community and the general public about the distinction between different types of tinnitus. The second is ensuring that each interventional neuroradiology department has a dedicated physician specialising in the evaluation of this symptom, as this activity requires significant consultation time and specific expertise in the anatomy and pathology of the temporal bone—knowledge that goes beyond the usual scope of most interventional neuroradiologists.

Without this expertise, there is a risk of repeating the intellectual error of oversimplification—assuming that all pulsatile tinnitus is due to TSS—which could lead to sinus stenting procedures without patient benefit.

For more information, visit the ‘pulsatile.tinnitus’ Instagram account.

Emmanuel Houdart is a professor and interventional neuroradiologist at Lariboisière Hospital (Paris, France) who specialises in the diagnosis and treatment of pulsatile tinnitus.