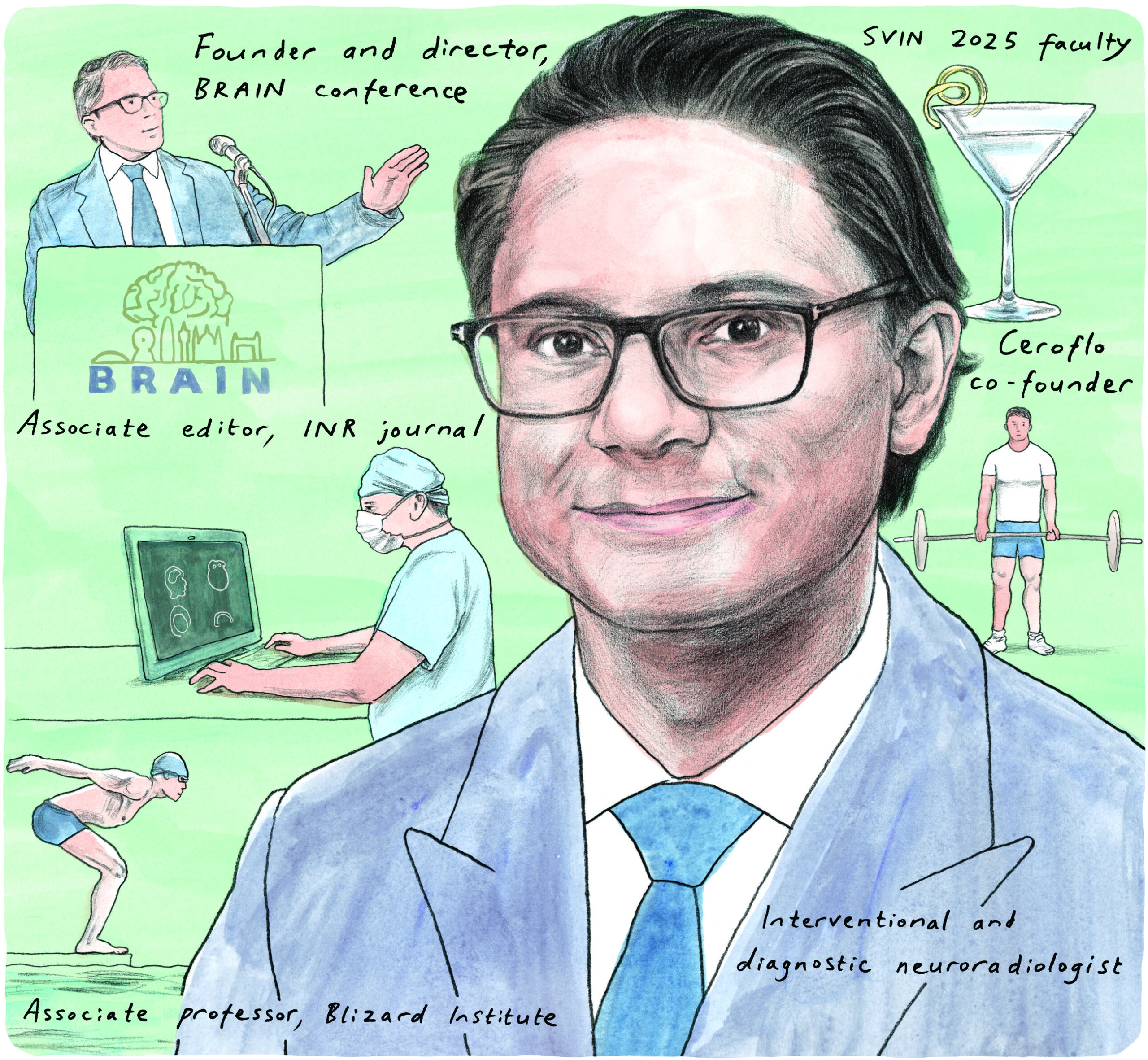

Having played a leading role in establishing one of the first 24/7 stroke thrombectomy services in the UK, and introducing the innovation-focused BRAIN conference several years ago, Paul Bhogal (London, UK) is a well-known, pioneering figure within the neurointerventional community. Here, diagnostic and interventional neuroradiology (INR) consultant Bhogal discusses his life as well as an array of other topics with NeuroNews.

What initially drew you to medicine, and the field of neuroradiology specifically?

I originally wanted to be a pilot and study aeronautical engineering, as I have always been fascinated by flying—and I would still love to get my pilot’s licence one day. Similarly, watching NASA launch rockets was always enjoyable and the idea of going into space was so compelling to me as a young boy. However, I realised that the most fun aspect of aeronautical design would have been working on the so-called ‘black projects’, which would have inevitably entailed weapons design. Making weapons that would be used to kill lots of people didn’t really sit easily with me, so I went in the complete opposite direction and decided to study medicine.

My father was a GP and medicine was always part of my life growing up. After graduating, I enjoyed medicine and surgery but preferred surgery; however, I could see the trend was going towards minimally invasive surgery and, when I had to decide which route to take back in 2007, it just seemed so obvious to me that pulling the clot out of a cerebral blood vessel would result in improved outcomes. At this stage, I hadn’t even been exposed to the world of INR but this seemed like something that would end up happening, and that would significantly impact the lives of patients. Just prior to entering radiology training, I had actually left medicine, and was planning a move into finance. I had sat my graduate management admission test (GMAT) and was preparing for interviews at several business schools when I was selected for a radiology interview. This was the only thing I said I would come back to medicine for, so it felt like a sign, and I went with it and never looked back. As Maverick from Top Gun would put it, “don’t think, just do!”.

Who have your mentors been and how have they impacted your career?

I’ve been lucky to have had a series of great mentors, most of whom I am still in contact with and I consider friends. In London, Andy Clifton and Jeremy Madigan took me under their wing, and taught me some important concepts, and the need to concentrate on anatomy and really think about what you are doing at each and every stage—both preoperatively as well as intraoperatively.

Following this, I went to work with Tommy Andersson, Michael Söderman and Patrick Brouwer, amongst others, at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden. This was honestly the best decision I have ever made in medicine and probably one of the best I’ve made in my life. They were so humble but had such a wealth of knowledge and would put up with all of my crazy ideas. As Tommy once said: Paul has 10 ideas a day, seven are terrible, the eighth is good, the ninth is great and the 10th only his mind could come up with, so you just need wait for the 10th idea and ignore the rest! This makes me laugh because it’s very accurate and I’m sure my colleague Levan Makalanda would say something similar. But, at the Karolinska, I learned so much and it was a place where we could think, question what we do and why we do it, and try to develop novel ideas and solutions to problems.

I later joined Hans Henkes in Stuttgart, who will no doubt continue to be a pioneer in the neurointerventional space for many years. Spending time with him was really eye-opening with regards to his thought processes and meticulous planning of procedures as well as following patients up. It was also with him that I really learned how to write papers, and we have about 60 publications together. I think publishing is very important, so I try to teach my fellows and registrars the value of writing.

Could you summarise how you developed and now maintain one of the UK’s first 24/7 thrombectomy services?

First, I need to pay respect to the teams that got their mechanical thrombectomy (MT) services set up before us: Charing Cross, St George’s and Stoke to name a few. As with all centres, we wanted to build our service in a sustainable manner but, when Covid hit and we saw that patients were suffering from strokes, we knew we had to help. We reached out to the various hospitals and offered an MT service if they needed it. We were perhaps the only department to expand during the pandemic! Simultaneously, the Brainomix team partnered with us and we managed to create a large artificial intelligence (AI)-linked service covering some eight million patients. As other centres have come online, our workload has thankfully come down to more manageable levels, but I’m proud to say that the Royal London team went above and beyond both during the pandemic and in the years since.

Why did you initially set up the BRAIN conference? And, has the overall goal of the conference changed in the years since its inception?

There are many reasons that drove me to set up BRAIN but there was one in particular. In 2019, my father passed away from a pontine glioblastoma (GBM). As I was caring for him and watching him deteriorate every day, I remember feeling so helpless and impotent; how could there be nothing I could do? With all the miraculous things neurointervention can achieve, why is there nothing for GBMs? After many years of research, the neuro-oncologists have not really improved outcomes for these patients, so perhaps it’s time for a different perspective. When I decided to go after GBMs, I knew this would require a novel strategy, both in terms of targeting the disease but also building momentum. There are numerous researchers who have been looking at this problem for many years: Nancy Doolittle, Edward Neuwelt, Prakash Ambady, Piotr Walczak, Peter Kan, John Boockvar etc. They are all approaching the problem from different directions but how often do we see them present at neurointerventional conferences? I saw that we needed a new forum to bring together people from different backgrounds with different pockets of knowledge and experience that could build the big picture we’ll need to defeat GBMs.

This is also why I developed the ‘story arc’ concept we follow at BRAIN—to help organise knowledge in one’s mind, with the aim of making it easy for attendees to not only understand complex topics, taught by the real experts, but also enable them to have those ‘eureka’ moments. We need people to explore their own ideas on new and challenging topics, with diversity of thought and opinion that is also rooted in science and collaboration. If BRAIN can spark these moments of genius, it will have achieved my main goal for the conference.

What can attendees expect from this year’s BRAIN conference?

BRAIN is known for having those story arc concepts. Different talks are delivered by different speakers, each of whom is typically an expert and has published on the topic they talk about. These talks intertwine to tell a story for the attendees. Some of these arcs are intertwining to form ‘grand story arcs’ across many BRAIN conferences, with the final conclusions yet to come. This year is no different and I would, as always, invite the audience to join us and come with an open mind—’ditch the dogma’, as I said a couple of years ago.

This year, we will be talking a lot about different drugs, and how we should start to look at them and their potential uses—VEGF, KRAS and BRAF inhibitors, for example, and how these may be of use in disparate diseases such as chronic subdural haematoma (cSDH), GBMs, and arteriovenous malformations (AVMs). We will be returning to the topic of GBMs, and I will hopefully be showing some of the preclinical and clinical research that I have been involved in targeting GBM with a combination of drugs, and using cannabinoids, which have some fascinating anti-cancer properties. Similarly, I hope that the talk on AVMs will be really enlightening for people with regards to what might be happening at a molecular level to trigger their formation and propagation, and whether there are options to target them using drugs. We will have new devices across a range of areas, and definitely some returning speakers and updates. Most of all, I hope it is fun and enjoyable with great food, engaging presentations, provocative discussion and lots of Christmas jumpers! Keep your eyes open on the London skyline for a big BRAIN surprise too!

Besides stroke thrombectomy and the ISAT trial, what has been the most important development in the neurointerventional field during your career?

Although still in the early days, I think brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) are truly revolutionary, and their potential uses are almost too great to imagine. They naturally raise ethical questions but, thankfully, there are far more intelligent people than me thinking about this. In my humble opinion, these devices could conceivably augment humans with an as-yet unknown upper limit to their potential. For me, most other things in our specialty don’t even come close to what BCIs can achieve and the next decades will potentially yield some fantastical achievements that pull in technological advancements across a range of disciplines.

Which areas of INR do you think will experience the greatest levels of innovation over the coming years?

I think there will be multiple things that intersect to create significant leaps. One is blood-brain barrier (BBB) modification and drug delivery for things like GBM and, potentially, other diseases too. My opinion has always been that proving efficacy of an interventional approach in a disease like GBM may actually open the door to other diseases, such as dementia—what if we have the drugs but we don’t have the drug concentration, for example? This is speculative but some early work has been done using focused ultrasound to open the BBB and showed that the concentration of an intravenous drug was higher in the hemisphere that had the BBB opened compared to the hemisphere that did not. What if we could transform dementia into a chronic disease for which you have an angiographic treatment once a year to halt progression? This isn’t my area of research or expertise but I don’t think it is beyond the realms of possibility.

AI is going to come along leaps and bounds, and I think the next generation of angiographic machines will have AI built into them to essentially act as ‘driver assist’, making procedures safer and faster, and possibly improving results. This will intersect with systems and devices designed specifically for robotic procedures. Similarly, I don’t believe the lab of the future will be purely angiographic. We are already seeing low-field magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), so why not start to develop imaging suites with multifunctional capabilities?

And, again, perhaps the biggest thing will be BCIs. Their possibilities in transforming patient lives are huge and, coupled with robotics, could mean tetraplegics walking again using an exoskeleton suit. BCIs could also be used for interventional psychiatry via modulation of specific brain areas, creating new options for the treatment of diseases like depression. This will require research across multiple specialties but I think the neurointerventional field could undergo some huge transformations and become one of the largest areas in all of medicine. But who knows, maybe these are some of the seven ideas that are no good…

What are your interests outside of medicine?

Weight training, mixology—I love a Vodka Martini—and cooking and experimenting with different flavours and ingredients. I enjoy learning new things, such as improving my ice skating, and going for walks in the countryside, in addition to spending time with my wife, Tuulia, and our baby, Eleanor. I’m also a James Bond fan; I enjoy watching the Bond films and have read all the books, hence my love for Vodka Martinis. I even have James Bond socks! I’m not a very fast reader so nowadays I tend to listen to audiobooks and to podcasts in short periods of spare time—when commuting, for example. I also enjoy listening to music, and I have an eclectic taste, from Abba, to acid jazz and house, with a healthy dose of ‘traditional’ jazz thrown in.

What is your favourite James Bond movie, and why?

This is a tricky question—there are so many great ones! As I have gotten older, I have begun to appreciate the Roger Moore movies, and Roger as Bond himself. He had the best one-liners and was arguably the most suave Bond. Moonraker has definitely got to be up there for me personally. I thought Daniel Craig made a really good Bond and his character seemed close to the one in the books. Casino Royal was really good and moved away from the over-the-top storylines at the tail-end of the Pierce Brosnan era. Who is my favourite Bond girl? For the answer to that, we need a Vodka Martini.

Having recently become a father, how have you attempted to balance parenthood with your busy work life?

Generally, I would say I am failing! But, ultimately, I love my daughter more than I could have ever imagined and she is 100% the highlight of my day. Modern life has many distractions and there is always more work to do or another important meeting to attend but, for me, the most important time will be that with my family. On my deathbed, I won’t regret missing a conference or a ‘challenging aneurysm’, but I will regret not spending enough time with my family, so it’s an easy decision tree.

FACT FILE

Current appointments:

- Founder and director, BRAIN conference

- Interventional and diagnostic neuroradiology consultant, St Bartholomew’s and Royal London Hospital

- Honorary associate professor, Blizard Institute

Education:

- 2016–2018: Interventional neuroradiology fellowship, Klinikum Stuttgart

- 2014: International fellowship, Karolinska University Hospital

- 2010: Fellowship of the Royal College of Radiologists (FRCR)

- 2008: Membership of the Royal College of Surgeons (MRCS)

- 2004: MBBS, University College London (UCL)

- 2001: Neuroscience BSc, UCL

Honours (selected):

- 2013: Hospital Corporation of America (HCA) International Travelling Scholarship

- 2004: Third place, TeachFirst Challenge National Finals

- 2003: First place, TeachFirst Challenge Regional Finals

- Principal investigator (PI) for ProFATE and VANS studies

- UK PI for DISTAL trial and Neva One registry