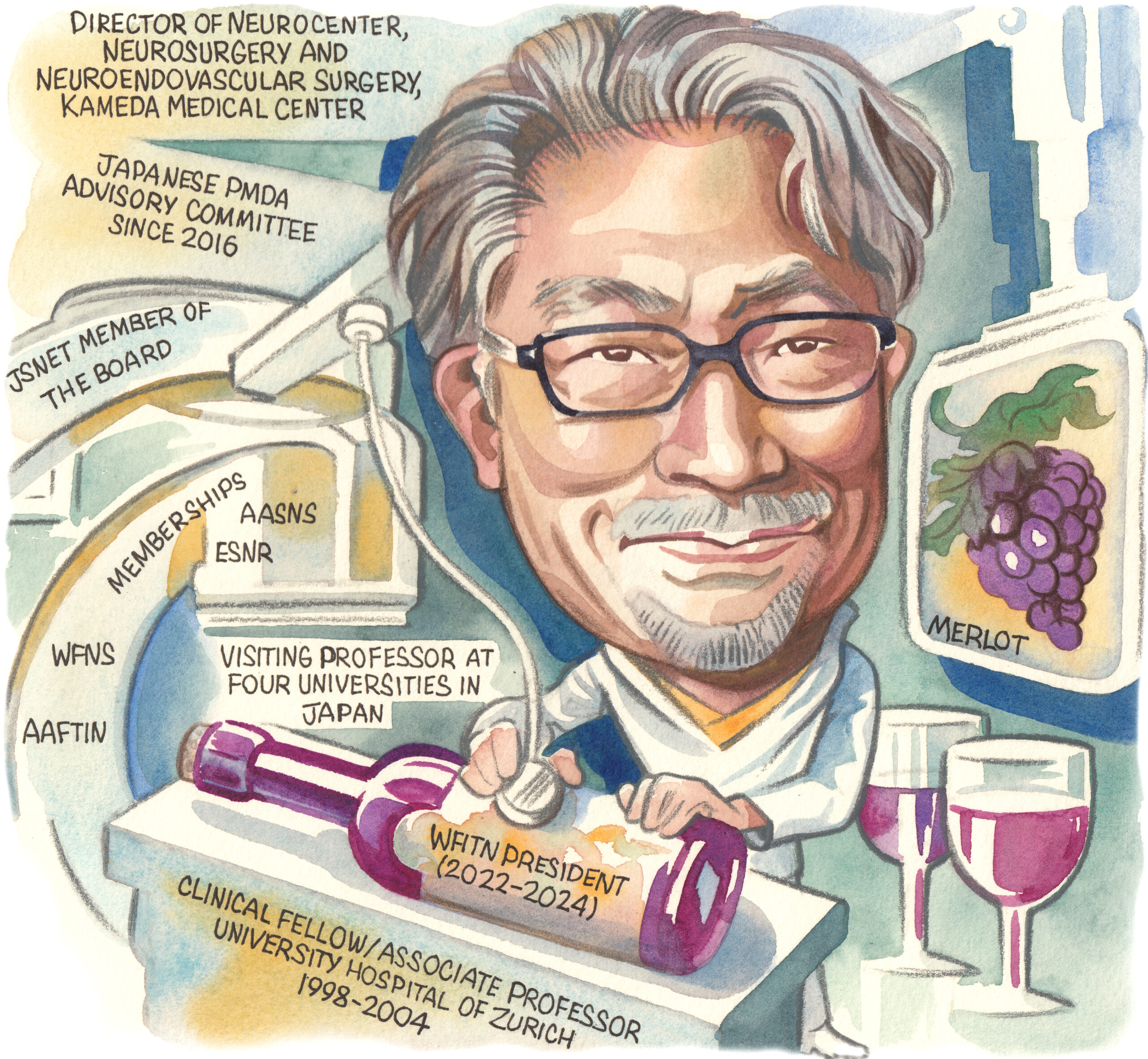

Michihiro Tanaka, director of Neurosurgery and Neuroendovascular Surgery at Kameda Medical Center (Chiba, Japan), speaks to NeuroNews to discuss the factors that have shaped his career as a neurosurgeon, his tenure as World Federation of Interventional and Therapeutic Neuroradiology (WFITN) president, and the current landscape of neurosurgical care.

What initially drew you to medicine, and the field of neurosurgery specifically?

Ever since I can remember, I’ve been interested in where the human body came from and what our ancestors looked like, and eventually became interested in palaeontology, and the study of dinosaurs, ammonites, and other things. As I studied mathematics, physics, chemistry and biology in junior high and high school, I became increasingly interested in the origins of living things and the history of vertebrates. If I was going to study vertebrates, I wanted to learn about the anatomy of Homo sapiens—which have a large brain—so I entered medical school without any doubts.

Who have your key mentors been and how have they impacted your career?

I have three people whom I consider to be my lifelong mentors. The first one is Isao Yamamoto, a professor in the Department of Neurosurgery at Yokohama City University School of Medicine (Yokohama, Japan) who worked on microanatomy under Albert Rhoton Jr at the University of Florida (Gainesville, USA) during his younger years. He was the mentor who taught me the importance and joy of microanatomy. The second one is Nobuo Hashimoto, who was the chief of the Department of Neurosurgery at the National Cardiovascular Center (Osaka, Japan) when I was a resident, and later became a professor at Kyoto University (Kyoto, Japan). He taught me the basics of microneurosurgery. The third is Anton Valavanis, who was a professor in the Department of Neuroradiology at the University Hospital of Zürich (Zürich, Switzerland). He taught me the fundamentals and clinical aspects of endovascular treatment in the brain, as well as embryological perspectives on brain arteriovenous malformations (AVMs). Regrettably, he passed away last May. He is the most important mentor in my life.

How did your time at the University Hospital of Zürich help shape your neurosurgical career?

When I initially took up my position in 1998, I was scheduled for a one-year clinical fellowship. However, as I had been studying German as a second language, Professor Valavanis offered me a salaried position (assistant professor) in 1999. By 2002, he promoted me to the position of Oberarzt (associate professor). In total, I had the opportunity to work at the University of Zürich for nearly six years. The university, founded in the 16th century, has produced many notable neuroscientists. It is famously associated with pioneers like Constantin von Monakow and Walter Rudolf Hess—and, in recent times, Mohamed Gazi Yaşargil, the founder of microneurosurgery, served as the university’s second professor of neurosurgery. My mentor, Professor Valavanis, was a radiologist who studied under Yaşargil and became the first professor of neuroradiology. Working at such a historic institution for nearly six years was a significant asset for me. Experiencing endovascular treatment of the brain in the mecca of microneurosurgeons was extremely important. It allowed me to learn surgical techniques but also gain an understanding of cerebrovascular disorders and the basics of clinical research within an interdisciplinary approach, which was very meaningful.

Could you outline your priorities as WFITN president?

The WFITN is a scientific society established in 1990 in Val d’Isère, France by Luc Piccard, Alejandro Berenstein, Pierre Lasjaunias, and others. It is a very historic association in this field and, as president, I have three main missions. The first is to consolidate neurointervention societies from around the world into a federation assembly. Currently, 18 societies from 16 countries participate in this federation assembly. One of my missions is to expand this assembly further, forming a community that transcends national and racial boundaries, and to provide multinational clinical research and educational programmes. The second mission involves managing the WFITN Educational Fund. This system uses funds collected from companies in various countries to assist young doctors from low-income countries who aspire to specialise in neurointervention. In 2023 specifically, seven doctors were able to participate in training programmes in Europe using this educational fund. The third mission is to organise WFITN anatomy courses. Knowledge of functional anatomy is essential for safe endovascular treatment of the brain. We are committed to holding training courses on anatomy relevant to endovascular treatment in various countries worldwide, helping young doctors in this field to perform surgeries safely.

What are the most notable ways in which neurosurgery has changed over the course of your career?

The Guglielmi detachable coil (GDC), introduced in 1997 in Japan, was indeed a revolutionary development. Until then, the cornerstone of cerebral aneurysm treatment had been clipping surgery via craniotomy, but the advent of this new device marked a significant shift. Clipping surgeries for aneurysms—particularly those in the posterior circulation like the basilar artery—were challenging areas for microneurosurgeons. The ability to treat aneurysms deep within the skull without craniotomy represented a major revolution in neurosurgical therapeutics. Encountering the GDC was a pivotal moment for me. It was then that I first became convinced that the future of cerebral aneurysm treatment would inevitably shift to endovascular methods, and this realisation was the impetus for my transition from being a microneurosurgeon to a neurointerventionist.

In the future, how is the relationship between open and endovascular neurosurgical techniques likely to shift?

Discussing gastric cancer as an example, the advancement of preventive medicine, such as the eradication of Helicobacter pylori—along with progress in endoscopic examination and treatment—has led to a situation where open gastrectomy for gastric cancer is now rarely performed. This trend suggests that the indications for open craniotomy will undoubtedly continue to diminish. In our hospital, traditional open craniotomies under the microscope have significantly decreased, being replaced by surgeries performed with neuroendoscopes and neuro-exoscopes. Surgical treatment is evolving towards an increasingly minimally invasive style. Regarding the treatment of cerebrovascular disorders, the role of craniotomies is expected to reduce further, with endovascular treatments becoming the mainstream. However, craniotomies using the next generation of operative imaging will still remain an important treatment modality for trauma and benign tumours at the skull base.

What are the biggest challenges facing neurointerventional care in Japan today?

Subspecialty dispersion among neurosurgeons is a significant challenge; Japanese neurosurgeons tend to be generalists, covering a wide range of responsibilities from surgery to postoperative management. This broad scope often leads to a dispersion of subspecialties. For instance, while cerebrovascular disorders are a primary focus for many, neurotrauma and neurocritical care are less emphasised. One survey indicated a decline in neurosurgeons specialising in neurotrauma and even fewer choosing neurocritical care as their subspecialty. The rate of older patients (octogenarians) undergoing neuroendovascular therapy has also increased significantly. This shift is likely due to Japan’s ageing population, which presents unique challenges in treatment approaches and outcomes.

Which piece of research you have been involved in has had the most significant impact within the neurosurgical space?

I contributed a couple of articles regarding the embryological consideration of dural arteriovenous fistulas (dAVFs)—vascular abnormalities that can be influenced by their embryological origin. In particular, dAVFs located in the falcotentorial area, which derive from the neural crest, have been identified as a risk factor for a more aggressive clinical course. This includes more significant clinical presentations, and a higher likelihood of cortical and spinal venous reflux. The neural crest origin of these dAVFs—particularly in areas like the olfactory groove, falx, tentorium of the cerebellum, and nerve sleeves of the spinal cord—contributes to their unique clinical characteristics and challenges in treatment. This highlights the importance of considering the embryological origins of dAVFs in their diagnosis and management.

Which areas are likely to have the greatest impact on neurosurgery over the next 10 years?

Enhanced imaging and visualisation techniques; the integration of robotics and artificial intelligence (AI); research in nerve regeneration and neuroplasticity; genomics and personalised medicine; neuroprosthetics, including brain-computer interfaces; and new neuro-oncology therapies and techniques in treating brain tumours, such as immunotherapy and targeted drug delivery. These areas reflect the convergence of technology, personalised medicine, and innovative surgical techniques, driving forward the field of neurosurgery.

Could you describe one memorable case and the effect it had on you as a surgeon?

In 1996, I encountered a remarkable case that profoundly influenced my career choice: a baby girl born with severe heart failure due to Vein of Galen aneurysm malformation. We successfully treated her with an endovascular approach on the third day and again at one month after birth. This intervention effectively resolved her heart failure and she experienced normal neurological development. Now, she is 27 years old, in good health, and gainfully employed. This unforgettable experience solidified my decision to specialise in neuroendovascular surgery.

What advice would you give to people embarking on a career in neurosurgery?

Embarking on a career in neurosurgery is a challenging yet immensely rewarding journey. It is as demanding as it is fulfilling, requiring a blend of intellectual capability, technical skill, emotional strength, and a profound commitment to patient care. As such, there is plenty of advice to consider. Ensure you have a strong grasp of the basic sciences, particularly anatomy, physiology and pathology. Be prepared to continually update and refine your knowledge, and surgical skills, to stay abreast of the latest techniques and technologies. Be prepared for long hours and demanding work schedules—resilience, perseverance and a strong work ethic are essential. Exercise excellent communication skills and empathy, as these are vital when dealing with patients and their families. Engage in research and academic pursuits that contribute to the field, but also enhance your understanding and open opportunities for career advancement. Build a network of peers and mentors, as guidance and support from experienced neurosurgeons is invaluable. Balancing work and personal life is crucial for long-term success and wellbeing, so take care of your mental and physical health. And, always prioritise ethical practice—the patient should be at the heart of all your decisions.

What are your interests outside of medicine?

A passion for wine, conducting genetic research on grapes, engaging in tea ceremonies influenced by Zen teachings, and playing Bach’s piano compositions.

What would you be doing for a living if you had not chosen a career in medicine?

Working as a farmer of grapes, especially pinot noir, and producing my own brand of wine.

FACT FILE

Appointments:

- 2022–2024: President, WFITN 2023–present: Director of Neurocenter, Neurosurgery and Neuroendovascular Surgery, Kameda Medical Center

- 2016–present: Advisory committee, Ministry of Health Labor and Welfare, Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA)

- Visiting professor at Tokushima University (2022–present), Tokyo Jikei University School of Medicine (2022–present), Fukuoka University Chikushi Hospital (2016–present), and Showa University of Medicine (2016–present)

Education:

- 2006: PhD, medical science, Yokohama City University School of Medicine

- 1998–1999: Clinical fellowship, Institute of Neuroradiology, University Hospital of Zürich

- 1994–1996: Residency, Neurovascular Surgery, National Cardiovascular Center

- 1985–1991: MD, National Yamanashi University School of Medicine (Kofu, Japan)

Clinical/research interests:

- Intracranial aneurysms

- AVMs

- DAVFs

- Head and neck tumours

- Spinal cord vascular malformations

- Carotid artery revascularisation