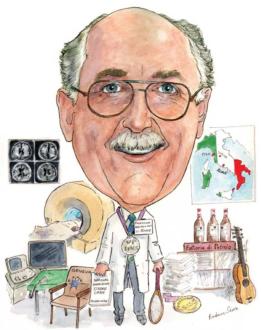

Gian Luigi Lenzi, professor of Neurology, University of Rome, Italy, has a passion for producing good Chianti! In this interview with NeuroNews, the vice president of the European Federation of Neurological Societies (EFNS) describes the early years of his career, what fascinates him about neurology and his intention to decrease the gap between senior and fellow professionals as this year’s chairman of the Programme Committee for EFNS in Geneva. Lenzi also gives young neurologists advice on how to “reach their destination”

How did you become interested in medicine?

My father was professor of Internal Medicine and dean of the Medical School in Siena, and my uncle was professor of Internal Medicine and dean of the Medical School in Bologna. I grew up listening to medical discussions, and I was fascinated by the intellectual reasoning that was behind diagnosis and therapy. I was, however, more interested in history and classical literature, and the struggle of which field to choose, continued to the last days. One primary goal was leaving my hometown and supporting myself financially in a university away from home and relatives. So, I landed at the Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa (presently St Anne University) through an application, where I obtained tuition, room and board.

What fascinates you about neurology?

At the interview for the Scuola Normale Superiore Medical School Fellowships, one of the professors who interviewed me quickly realised that my knowledge of biology was poor, since I had studied classical literature in high school, but that I had good knowledge of history. Therefore, the subject of the interview was no more the cerebellum, but the Paix of Chateau Chambresis and its consequences for Europe. This professor was the Nobel candidate Giuseppe Moruzzi, and he asked me to join his world-renowned Institute of Neurophysiology. From 1961 to my graduation in 1967, and for three years more, I worked on experimental neurophysiology. However, the call to do clinical work was too strong, and my relationship with the professor I worked under had deteriorated, so in 1970 I joined the Postgraduate Neurological School in Rome, chaired by Prof Cornelio Fazio. I slept in a small room in the Department of Neurology, I performed night duties to support myself, and I helped to develop a neurophysiology laboratory.

Who were the people who inspired you in your career, and what advice of theirs do you remember today?

When I graduated in neurology, in 1972, the chances of obtaining a position in the University of Rome were very low, since I had joined Prof Fazio’s school only two years before, and many other young fellows were in line before me. Prof Fazio suggested I could join his pupil Cesare Fieschi at the University of Siena. After 13 years away, I was returning to my hometown, to find the same problems I had in high school years, and a very active and bright “boss” who asked me to accept my position of “last of the last” and suggested that I learn quickly to remain silent as much as possible. (First advice: humility). And I complied.

In 1976, I won a fellowship to spend six months abroad, and at that moment Prof Ferruccio Fazio, the son of Cornelio and a good friend from Pisa University, who was working in London, suggested that I changed the subject of my research project from the vestibular system to some interesting developments in the study of cerebral metabolism exploiting short lived isotopes such as oxygen15 (Second advice: novelty seeking). The results of these six months of hard work in London at the MRC Cyclotron Unit, with Terry Jones (Third advice: when the rod is hot, work with your hammer), were commented by my Siena “boss” as “you had a good holiday with these small clouds” (i.e. the brain images of my patients studied with O15 and a gamma-camera). But the two major 1977 congresses on CBF, in Salzburg and Copenhagen, awarded my presentations with an absolute success and allowed me to jump from the “last of the last” to the first position when Cesare Fieschi, in November 1977, moved from Siena to Rome, and asked me to join him (Fourth advice: pardon the offences without forgetting them, and move on). (And, young fellow neurologists, if you need more profound advice, I will privately tell you the joke of the sparrow, the cow and the fox…).

Could you identify a few exciting developments in neurology today?

Neurology is full of exciting developments, from genetic and genomic studies linking response to therapy to genotypic aspects; to neuroimmunology, with vaccinations against MS and Alzheimer’s being already tested in patients; to stem cells therapy; to functional neuroimaging; to endovascular techniques for stroke. But the more striking development is the increasing bulk of data that are showing the neurobiological basis of psychiatric disorders and of psychological traits. How the personalities of the newborns are determined through early experiences, through mother-child relationships. All this may seem outside classical neurology today, but in my opinion, it will be the core of the “new” neuropsychiatry of the future.

As a large body of your research has been in stroke, what are the current most interesting concepts in this area?

Stroke is the second leading cause of death and the first cause of invalidity in the world. Since 80% of the strokes are due to ischaemia, the relevance of the therapeutic window is of the utmost importance. Time is brain. However, even in the best of situations, no more than 25% of acute ischaemic strokes actually receive this time-linked therapy (today the percentage is well below 10%!). Therefore a similar or stronger effort has to be made towards the treatment of the “late-arrivals” strokes, including brain haemorrhages. Also 50% of strokes will remain with a deficit after 12 months–we need to improve this poor result, offering patients, their families and society a better outcome. Neurorehabilitation needs to be deeply revisited with scientific approaches. Interactions between drug therapy and neurorecovery have to be revised using a scientific approach.

Can you comment on the importance of imaging in neurology?

Neuroimaging has changed neurology. It is hard for me to remember how we managed to proceed in the 70s and in the 80s without neuroimaging. However, today many neurologists choose to leave neuroimaging to neuroradiologists and radiologists. The interpretation of neuroimaging needs a deep knowledge of the brain’s physiology and physiopathology. It needs a deep neurological culture. I urge the young neurologist to learn as much as possible about these techniques, to interpret scans directly and to request neuroimaging studies for his/her patient with a precise knowledge of the “whys” and of the “ifs”.

Could you describe some memorable cases you have treated, and the outcomes?

I indulge myself and my students with cases that have been sent to my ward from the SU of my hospital as “non-vascular” cases and they have turned out to be, not only vascular, but also treatable and then treated, with a good outcome. But I also present to my students cases where my initial diagnosis was “not favourable” and the intense application of my juniors turned it to “favourable”, with a clear-cut positive result for our patients. All this is to give two pieces of advice: a) never accept a no-return diagnosis made by others; b) be ready to listen to and consider your colleagues’ ideas.

What is the most interesting paper you have come across recently?

I was very interested in an Italian paper in Science 2010, linking a small lesion in the rat’s parietal lobe to Proust visually elicited olfactory memories. I was struck by the nearly complete absence of any relationships with the “mirror system” described in primates by Gallese and Rizzolatti.

Which technique or technology had a profound influence on your career?

From 1977 to 1982, I worked actively to develop positron emission tomography (PET) and later SPECT. However, in the following years I could not, due probably to my poor diplomacy, collect the funds necessary to establish a PET centre in my university or to create a group of local academic friends mandatory to reaching that goal. I had to join groups in Milan and Los Angeles to satisfy my scientific questions. Only in the last years, the with fRM neuroimaging, have I had the chance to be directly involved in this research. At the age of over 60, it was probably too late. I have been told that next year, in 2011, a PET Camera should reach our university hospital, to be devoted to oncological work-ups. At the age of more than 65, definitely too late for me!

What do you hope to achieve as Geneva CPC for EFNS this year?

In my opinion, there is too large a distance between the (more or less) young neurologists sitting in the halls of the conference and the speakers giving a lecture. I would like to exploit the Geneva Congress to decrease this gapslightly. The mechanisms that are behind the formation of the congress scientific programme are very democratic, but their final result is that the majority of the speakers are “retired” academicians. As Geneva CPC, I will send a message to the participants directly.

Do you have a message for young neurologists?

Always be positive, energetic and active, but remember to listen, understand and, “interiorise” messages that other people are trying to give you. And, please leave off from“prima donna behaviour”. The approach to medical research, with neurology as one of its best examples, should be as the slow but continuous progression of the humble pilgrim on the Road to Santiago. Fatigue, humility, sweetness, and the strongest confidence will make you reach your destination.

What are your interests outside of medicine?

The more important is the growing of a good wine, in an estate in Chianti Classico (Tuscany) region owned by my family for a couple of centuries. I like to spend time with my family (four daughters and two granddaughters, so far), friends, and enjoy good books, good food and good red wine.

After the EFNS congress in Florence, I had the pleasure of playing host to the president and the staff and a few members of the management and programme committee at the Petroio estate for a direct tasting of the “fiorentina” beefsteaks which I cooked in front of all the guests.

I play tennis twice a week, and I walk, both in the bushes of Chiantishire with my dog and in the mountains of North Spai and on the “camino” for Santiago. I refresh the mechanisms of my memory by playing Bridge. In the Department of Neurology, I am the oldest of the remaining professors of neurology, and will retire happily in 2013, going straight back to my beloved Chianti countryside.

Fact File

Born in Siena, Italy, 24 October 1943

MD Pisa University,1967

1967–1970 Fellow Institute Neurophysiology, Pisa University

1971–1972 Postgraduate Neuropsychiatric School, 1st Roma University

1973–1977 Assistant Professor in Neurology, Siena University

1977 Senior Registrar, Cyclotron Unit, MRC, Hammersmith Hospital, London UK

1978–1985 Associated Professor in

Neurology, University of Rome

1979–80 MRC PET Unit, Hammersmith Hospital, London, UK

1985–2010 Professor of Neurology, Dept of Neurology and Psychiatry, University of Roma, Italy

Main themes of research

Brain work in normal conditions, in ischaemia, and in neurorecovery.

Lenzi has introduced into the clinical workup new neuroimaging techniques (PET, SPECT); and currently works with neurosonology and fMRI, on the role of the “mirror neurons”. He is coordinating the National Commission on Stroke Care.

Author of more than 180 papers in peer-reviewed journals

Past-president of the Italian Society for the Study of Stroke (SISS), he has been chair of the PC of the Federation of the European Neurological Societies (EFNS), for the years 2005–2009, and presently he is vice president of the EFNS.

Lenzi is consultant to the Secretary of Health (Italy), in the CSS and the AIFA Agency.