The past 18 months have seen a radical shift in clinical evidence supporting the role of middle meningeal artery embolisation (MMAe) within subdural haematoma (SDH) treatment, with no fewer than four randomised controlled trials—three of which were first presented at the 2024 International Stroke Conference (ISC)—demonstrating its benefits alongside the current, surgical drainage-based standard of care. A key limitation that endures, however, is the fact that haematoma drainage and embolisation are still widely performed as two separate procedures. Against this backdrop, Luis Savastano (University of California San Francisco [UCSF], San Francisco, USA) and his colleagues have been working to develop a novel technology that could enable these two operations to be completed via a fully endovascular, ‘two-in-one’ approach. With initial findings on the technology set to be disclosed at this year’s ISC (5–7 February, Los Angeles, USA), Savastano speaks to NeuroNews alongside Pedro Lylyk (Clinica la Sagrada Familia, Buenos Aires, Argentina)—who performed the first-ever minimally invasive surgeries incorporating this novel approach in human patients—to discuss the “quantum leap” it could represent in SDH care.

What is currently the greatest unmet need in the interventional treatment of subdural haematomas?

Savastano: A non-acute or ‘chronic’ SDH (cSDH) is a recurring collection of blood on the brain’s surface, which has an in-hospital mortality rate of 16.7% and a one-year mortality rate of 32%. Surgical drainage or ‘clot evacuation’ of cSDH—which is the primary treatment for this condition and one of the most common neurosurgical procedures in the USA—is associated with high recurrence rates, greater than 20% in some patients, and complications.

MMAe is an emerging treatment for cSDH in which embolic agents are injected into the MMA to decrease the blood supply to the haematoma and prevent re-accumulation. Multiple randomised clinical trials have recently demonstrated a reduction of SDH recurrences in patients undergoing MMAe in addition to surgical drainage. With the rise of MMAe, the ‘two-step’ management that combines surgical clot evacuation for rapid brain decompression alongside endovascular MMAe to prevent rebleeding as a surgical adjunct is rapidly becoming the leading paradigm in symptomatic cSDH treatment. Although effective in preventing recurrences—and rapidly becoming popular—the double-intervention strategy of surgery plus MMAe has several fundamental issues, such as:

- It carries all the risks and problems of surgery, including postoperative infection, bleeding, seizures, pain, intensive care unit (ICU) stay (typically two days or more when drains are used), more extended hospitalisations, high recurrence, the need to discontinue antiplatelet and anticoagulant agents (potentially subjecting patients to serious ischaemic complications), and the social stigma of brain surgery

- It requires two different procedures, typically done by two different teams in two different places; neurosurgeons draining the SDH in the operating room (OR) and endovascular neurointerventionists embolising the MMA in an angiography suite—both frequently done under general anaesthesia, which is detrimental in elderly and fragile patients

- Increased levels of costs, healthcare utilisation, and hospital stay

We thought that a technology capable of draining the SDH and embolising the MMA in a single, fully endovascular approach was urgently needed and could result in a paradigm shift in treating this condition. The problem was that this ‘moonshot’ required a purposed technology to obtain safe, easy and consistent trans-arterial access into the intracranial space, which had never been attempted before.

Could you briefly describe the technology you and your team have been working on to meet this need?

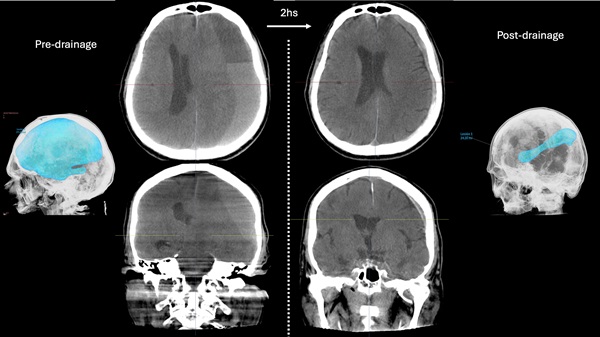

Savastano: We have been working on the first minimally invasive technology for ‘trans-vascular’ surgery that enables MMAe and cSDH drainage in a single, fully endovascular intervention. In a typical case use, the procedure starts by navigating catheters over wires into the MMA from peripheral arterial access using conventional endovascular techniques, followed by delivery of embolisation agents to occlude the distal vasculature. At this point, a proprietary wire is delivered through the catheter into the MMA lumen, and actuated to perforate through the arterial wall and dura. The wire has unique features that allow it to self-orient and control perforation depth. The advancement of the wire creates a corridor from the MMA to the subdural space, through which a catheter is guided into the subdural haematoma and used to drain the fluid. After drainage, the system is pulled back into the MMA, the trans-vascular access is occluded, and the whole system is removed from the patient’s vasculature, concluding the procedure. Hence, MMAe and SDH drainage are seamlessly integrated into a single, minimally invasive endovascular procedure.

Could you also summarise where this idea came from, and how long you’ve been working on it and refining it up to now?

Savastano: We started to work on this technology intensively about five years ago, and we were immediately faced with many challenges that we had to overcome to turn the idea into reality. The premise of navigating natural vascular corridors in our bodies into the head, gaining trans-vascular access to the brain surface, and treating non-vascular conditions, was fascinating—but, how to do it was completely uncharted. Since the pioneers of our specialty started delving intravascularly with wires and catheters a few decades ago, the neuroendovascular field has reached a remarkable degree of technical and technological sophistication. However, this development has mostly evolved within the intravascular boundaries and focused on solving vascular problems, such as aneurysms and arterial blockages. We wanted to break through the vascular walls’ limits, and open up a new frontier to access the brain and treat non-vascular conditions; something that we call the ‘trans-vascular’ field.

We ran two demanding programmes in parallel to start conquering this new horizon (from which the company’s name, Endovascular Horizons, is derived). On one side, we had to develop the first-in-class technology to accomplish something deemed impossible and full of engineering oxymorons, for which we recruited the absolute top wire and catheter engineers into the company. On the other side, with the support of the National Institutes of Health (NIH)—through the Blueprint MedTech Program—we partnered with the UCSF Transcatheter Neurosurgical Technologies Lab to make use of their best-in-class preclinical testing platforms including 3D phantoms, large animals and human cadaveric models. These parallel efforts supported extensive prototyping and iterative testing, leading to the maturation of an optimised technology that recently provided very positive clinical results.

What stage of clinical evaluation is the technology at right now, and how has it performed in testing and studies to date?

Savastano: The system is currently under evaluation in a first-in-human study with Pedro Lylyk and his team at Clinica la Sagrada Familia. This is a safety and feasibility study to evaluate the technical and clinical success of trans-vascular drainage of SDH plus MMAe with long-term follow-up. We are happy to report that this study shows that our technology consistently enables a safe trans-vascular access to the subdural space, achieving a major volumetric reduction of subdural haematomas with a dramatic midline shift and rapid clinical improvement. Moreover, patients are doing remarkably well at a long-term follow-up of six months, with no SDH recurrences observed to date.

What is your eventual goal for this technology—and how do you believe this approach will fit in alongside traditional MMA embolisation, given the recent results from randomised clinical trials?

Savastano: The immediate goal of this technology is to radically improve the care and outcomes of patients with SDH, most of whom are elderly and vulnerable, and we are actively working with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to make this therapy available in the USA as soon as possible. This goal is monumental for patients—since most are septuagenarians or octogenarians—as well as patients’ families, healthcare providers, and payers. However, the technology we are developing is fundamentally a way to access the intradural space and brain without opening the head. Trepanation, which involves drilling a hole in the skull, is the oldest surgical procedure known to humanity, extending back over 5,000 years. Despite thousands of years of medical and technological improvements, we continue to open holes in patients’ heads for most neurosurgical problems. The ultimate goal for Endovascular Horizon’s technology is to enable a new era in medicine where the natural vascular corridors in our bodies are used to access the brain ‘trans-vascularly’ to treat non-vascular conditions (for example, draining SDH), deliver drugs and therapeutics, and implant devices like neuroprostheses and brain-computer interfaces.

Very recently, randomised controlled clinical trials have demonstrated that adjunctive MMAe, in addition to surgery, is associated with a significant reduction in non-acute SDH recurrences requiring surgical drainage compared to surgery alone. This is great, but the tradeoff is the need for two interventions with associated risks and discomfort, prolonged ICU and hospital stay, and drastically increased medical care costs. Our technology was built to enable SDH drainage by gaining intradural access through the MMA itself following embolisation in the same session. This is a quantum leap compared to the current standard of care that demands the surgical creation of holes in the head—sometimes with temporary implantation of drains—or other potential approaches that could rely on a trans-venous route and end up doubling the amount of required work, risks, procedural time and devices needed.

All of the discussed benefits of this technology translate, in turn, into better outcomes and accelerated recovery for patients. Furthermore, all the procedures performed to date have been done with patients fully heparinised, suggesting that the endovascular SDH drainage during MMAe could be done without interrupting anticoagulation and antiplatelets, thus minimising perioperative cardiovascular events. Finally, there is a large and growing neurointerventional workforce capable of safely performing MMAe that could easily incorporate the endovascular drainage of SDH in their practice. By providing a new treatment option to a large group of physicians, we expect to decrease the need to transfer patients to tertiary centers and improve timely access to a lifesaving intervention for communities that have historically suffered from a lack of readily available, specialised neurosurgical care—including under-served rural populations, people with lower socioeconomic status, and racial and ethnic minority groups.

If this technology continues to demonstrate promise and produces benefit in patients, what do you envisage as the role for open neurosurgical approaches in non-acute SDH moving forward?

Savastano: In the limited clinical experience to date, we have intentionally been very inclusive to capture all types of non-acute SDH, and the results have been very promising—even in those cases that would have conventionally required craniotomies, such as in multiloculated SDH, very large SDH and acute-on-chronic SDH. We are therefore bullish in our projections, and we anticipate that most non-acute SDHs will be subject to endovascular drainage as the first-line treatment. We envision that open approaches for non-acute SDH will be valuable as a rescue procedure when endovascular drainage and MMAe are not successful in achieving sufficient brain decompression to resolve the patient’s symptoms rapidly; in the rare circumstance of SDH recurrence after endovascular treatment; or when the anatomy of a particular patient means the embolisation is not technically possible or is contraindicated.

Having become the first physician in the world to use this device in human cases, what are your initial thoughts on its performance and characteristics?

Lylyk: The use of the system to perforate and drain the SDH is very intuitive and straightforward, and only requires basic endovascular skills—basically, embolising the distal MMA branches, then pushing a wire through the dura, and then advancing a microcatheter co-axially over the trans-vascular wire for drainage. The components of the system are compatible with most guide catheters and microwires currently used for MMAe, and the drainage itself only adds a few minutes to the overall procedure (but saves a trip to the OR for surgery and prevents ICU days). I think that all neuroendovascular surgeons will be able to rapidly learn and incorporate this technology in their practices, especially now that MMAe has become a routine procedure in most places.

Further down the line, if this technology demonstrates positive results in clinical trials and is used more widely, how much of an impact could it have on SDH care?

Lylyk: It will be transformational. I expect that, within the next decade, most SDH will be treated endovascularly with Endovascular Horizons’ technology. Why would you do two different procedures when you can fix the problem with one solution? When we discuss the possibility of participating in the trial with our patients and their families in Buenos Aires, they immediately understand the benefits of avoiding a second procedure—especially when it involves drilling holes in the head. In addition, the clinical outcomes so far have been outstanding. We see patients rapidly improving to their baselines, spending fewer days in the hospital, and not returning with SDH recurrences or other problems after discharge. This technology is opening a new era in minimally invasive neurosurgery, and treating SDH is the first step. I have been involved in first-in-human clinical experiences of neuroendovascular devices for more than 30 years. I was fortunate to witness those breakthrough innovations that have radically transformed the field; this is one of them.