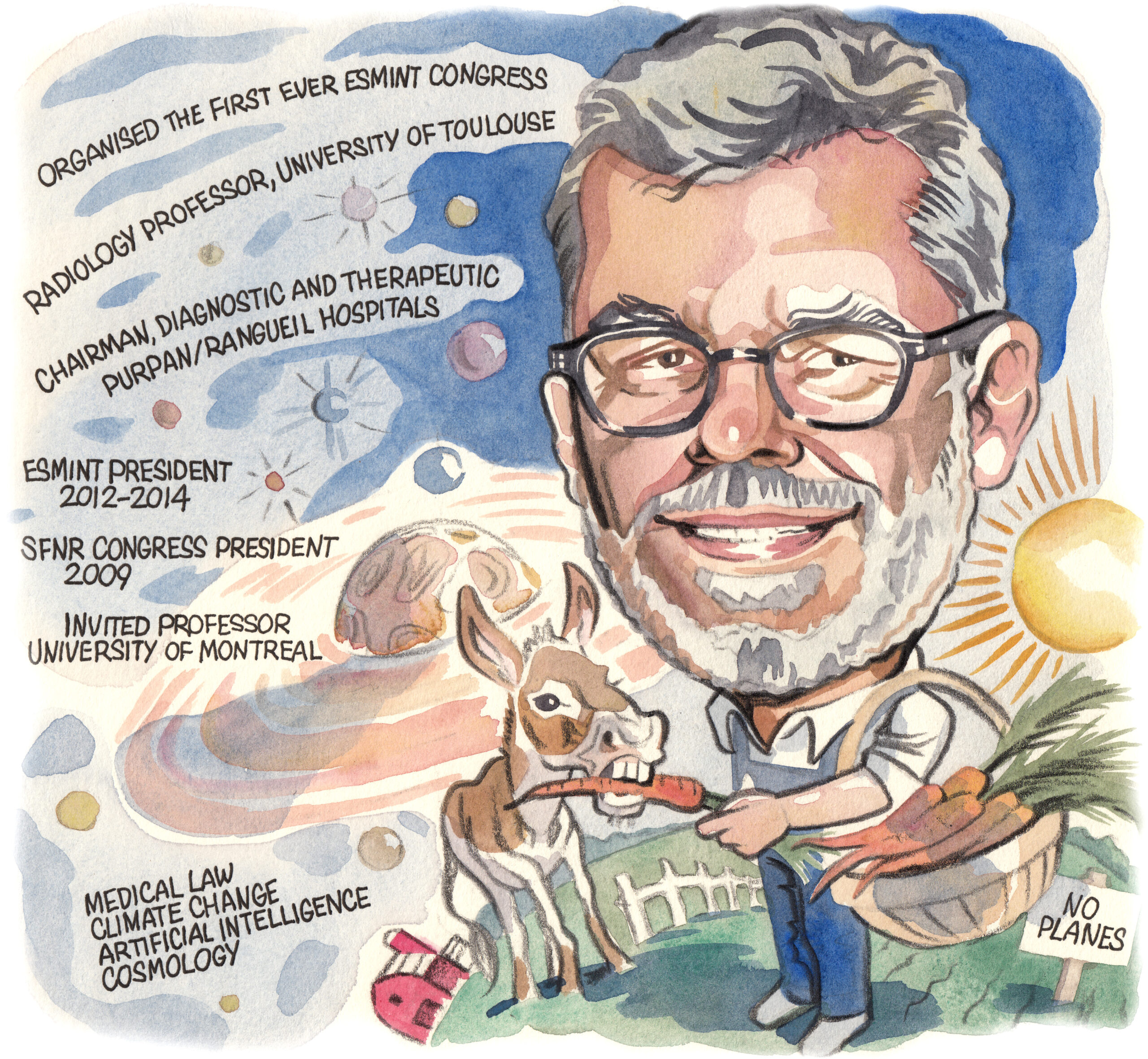

Throughout his life and career, Christophe Cognard (Toulouse, France) has always sought to help advance the interventional neuroradiology (INR) space, and make the management of neurovascular diseases as multidisciplinary and collaborative as possible. Notable examples include his efforts as president of the first-ever congress of the European Society of Minimally Invasive Neurological Therapy (ESMINT) back in 2009, and his contributions to numerous clinical trials that have served to further the treatment of intracranial aneurysms and brain arteriovenous malformations (AVMs). His non-INR interests are both extensive and eclectic too, ranging from medical law and climate change to the origins of the universe itself. Here, Cognard sits down with NeuroNews to discuss all this and more.

How did you first become interested in medicine?

I have never really been interested in medicine. When I was an adolescent, I was intrigued by fundamental physics, brain functioning, and protection of oceans and forests. I finally chose to go to medical school to become a psychiatrist. During my second year of medicine, I was also in my first year of philosophy at Sorbonne University (Paris, France), but I stopped after six months as I was not able to do both simultaneously. I did a fellowship in Paris, taking turns every six months in several psychiatry departments.

How would you say your time doing military service has impacted your medical career?

I did my military service over a period of 16 months in the West Indies, at Centre Hospitalier Universitaire (CHU) de Pointe-à-Pitre (Les Abymes, Guadeloupe), as a young psychiatry consultant. This was a very interesting experience as I was personally in charge of patients—often from their emergency arrival at night with an acute delirium, for example, to their long-term follow-up months after in countryside dispensaries. At that time, I came to understand what the real ‘on-the-ground’ psychiatry discipline was. I particularly understood the chronicity of the diseases, and the low impact and efficacy of the therapists. To be a psychiatrist, you must be patient and modest, and accept that you will help patients rather than saving them.

Why did you decide to abandon psychiatry in favour of INR?

I wanted to be at the interface of psychiatry and neurobiology in order to better understand the functioning of the brain, and the causes of mental disorders. But, after three years of practising psychiatry and one year of research work in a department of neurobiology— involving purification and solubilisation of the 5HT1a serotonin receptors of rat hippocampi—I understood that, at that time, we were very far away from filling the gap between mental illness and neurobiology. I should have been more insistent as, today, it is a fascinating field.

Who have been your key mentors and how have they impacted your career?

After years of doubts and hesitations, I found my way when I was resident in Lariboisière Hospital (Paris, France) in the team of Jean Jacques Merlan. It was a marvellous team full of passion, desires and the will to invent a new field in medicine. Alfredo Casasco was my first mentor. Then, Jacques Moret—with whom I spent three years in Rothschild Hospital (Paris, France)—taught me all of what I know today.

What are the most notable changes you’ve observed in INR practice during your time as a radiology professor?

The development of new devices has deeply changed our practice. Performing long injections of a large volume of liquid embolic, such as Onyx (Medtronic), through detachable catheters has changed the game—even if we still need to master glue injection. Flow diverters have been a revolution, allowing us to treat previously untreatable aneurysms e.g. giant, fusiform, dissecting. The Woven EndoBridge (WEB; Microvention/Terumo) has allowed us to treat very large-neck bifurcation aneurysms much more easily and in a very safe way. And, after years of technological failure, a stent developed to treat unruptured aneurysms (Solitaire [Medtronic]) has finally been used to reopen occluded arteries, and this perfect example of serendipity has revolutionised the treatment of stroke.

The development of new devices has deeply changed our practice. Performing long injections of a large volume of liquid embolic, such as Onyx (Medtronic), through detachable catheters has changed the game—even if we still need to master glue injection. Flow diverters have been a revolution, allowing us to treat previously untreatable aneurysms e.g. giant, fusiform, dissecting. The Woven EndoBridge (WEB; Microvention/Terumo) has allowed us to treat very large-neck bifurcation aneurysms much more easily and in a very safe way. And, after years of technological failure, a stent developed to treat unruptured aneurysms (Solitaire [Medtronic]) has finally been used to reopen occluded arteries, and this perfect example of serendipity has revolutionised the treatment of stroke.

How did you come to lead the ESMINT congress in 2009?

The society was created by James Byrne, Daniel Rüfenacht and Jacques Moret, and they asked me to organise the first congress. I was president for two years, then co-president for four years, and then I decided to resign as I thought the congress should not be organised by the same guy for years, but that the presidents should change to represent all of the diversity of European practice. When working for ESMINT, I spend all my time trying to do my best to make it a multidisciplinary society gathering neuroradiologists, neurosurgeons and neurologists together in harmony.

How do you think the society and the congress have evolved in subsequent years?

ESMINT has become like the Society of NeuroInterventional Surgery (SNIS) or European Stroke Organisation (ESO)—one of the most important neurovascular societies in the world. It organises an annual congress, two European courses on INR and ischaemic stroke treatment, diplomas, and training with fellowships and e-fellowships. The most important thing is that ESMINT never promotes one lobby but is at the interface of all neuroscience disciplines.

Could you outline why you recently became an expert in legal medicine?

Physicians are more and more concerned about legal issues. Eventually, physicians can end up doing bad medical practices because they are too afraid of being prosecuted and ignorant about the law. I wanted to understand both sides of the coin. I spent two years at university learning about law in medicine and, today, I really like to defend patients and families as a legal expert.

What are the most impactful studies you’ve been involved with throughout your career?

ISAT was revolutionary, showing that coiling an aneurysm is better than clipping it. ISUAT was a very low-level study but it had the merit to show that most unruptured aneurysms should not be treated—even though, today, we still treat way too many aneurysms that should only be followed. ARUBA was another very low-level study, but it showed us that embolising unruptured AVMs is dangerous and that surgery, if possible—or abstention—is often better. And, indeed, after 20 years of attempts and failure to treat ischaemic strokes, the five big trials (MR CLEAN, ESCAPE, REVASCAT, SWIFT PRIME and EXTEND-IA) produced results that were breathtaking and have changed the world. In addition, trials involving the late window, large cores, posterior circulation and other stroke types have followed. Today, there are also the recent studies on subdural haematomas as well (EMBOLISE, STEM and MAGIC-MT).

How would you assess the current landscape of INR, and how do you envisage the specialty changing over the next 10 years?

INR started as an intimist specialty dealing mainly with cerebral haemorrhagic disease not amenable by surgery in the 1980s. It became the gold-standard approach for aneurysms in the 1990s and has since become the way to treat large-vessel stroke. Today, embolisation is set to also become a treatment of choice not only for subdural haematoma but intracranial hypo/hypertensions and pulsatile tinnitus too.

But, I have some concerns (I sometimes feel like an old, conservative neurointerventionist). Our practice depends on technology, yet technology is somehow becoming more important than the clinical rigour and savviness of a skilled, trained and humble clinician. The fast pace of new devices entering the market sets up a sort of fanatic and less-considered adoption of novel technologies. I observe an escalation of new ‘stuff’—an increasing pressure on clinicians to use the latest, trendy thing and abandon technologies that have shown efficacy through the years, and also have the advantage of keeping the price of the procedure stable or even decreasing it compared to newer devices.

The choice of contemporary technologies might be influenced by non-clinical reasons, such as a superficial aim of popularity exacerbated by professional and social network dynamics, or more obscure and as-yet unregulated agreements between clinicians and industry players. Who would have imagined, years ago, that numbers of followers and the ‘like-imperative’ could become more important than the H-index, which translates the respect and consideration of our community of scientists and peers? We’ve gotten used to the idea of being called key opinion leaders (KOLs) or even, imagine, a key online opinion leader (KOOL). I wish we could revise the process that makes us opinion leaders or opinion followers; mainly, I urge my colleagues—young and old—to value and cherish the independence of their opinions, and spend a lot of time and energy on working to critically form their own opinions. It takes study, and exchange, and sometimes discussions and the overcoming of differences and evolution of experiences. Let’s not give industry or anyone else the power to decide who is an opinion leader and who is not.

The risk I see in abandoning coils, balloons and stents for newer technologies is that we might lose skills. Treating an aneurysm with intrasaccular devices or flow diverters makes the procedure easy; the use of 3D-printed models or software to rehearse the procedure in advance makes it easier still. But, the cost of a procedure escalates and operators lose their skills using devices that can be more dangerous or less efficient—except when used for the specific situations they have been developed for—and much more expensive.

What would your main pieces of advice be to aspiring INRs?

Be human. Spend time with and take care of your patients, and discuss with them. Don’t be too fascinated by novelties, techniques, devices and industry innovation. And, like an Englishman in New York, “be yourself, no matter what they say”.

If you required a neurointerventional procedure, which physician would you want to see leading your treatment?

Anyone—whatever their nationality, religion, colour, sex or specialty (neurologist, neurosurgeon, neuroradiologist etc.)—who is reasonable and properly trained, and who is not inclined to do technical acrobatics but able to manage all techniques and devices, including the old-fashioned ones.

Could you outline any particularly interesting research you’ve seen recently?

Research on understanding the universe: black holes, dark matter, curvature of space-time. What was there five minutes before the big bang? And, artificial intelligence (AI). What will be the robots’ mental illnesses? Specialists are already speaking about ‘AI hallucinations’.

What are your hobbies and interests outside of medicine?

I’m very concerned about carbon dioxide and climate change. I have given several conference talks about this fear for humankind in the short term. I don’t understand the behaviour of humans, and the blindness and obscurantism to be able to destroy their own environment. For me, ‘climate sceptics’ are like flat-earthers, creationists or antivaxxers. I will give a talk at the next European Society of Neuroradiology meeting on the psychology of climato-scepticism. I stopped flying five years ago, and now spend my time on a farm with donkeys, ships and dogs, enjoying a vegetable garden and the beauty of life!

FACT FILE

Current appointments:

- 2014–present: ESMINT Continuation Committee

- 2002–present: Chairman, Department of Diagnostic and Therapeutic Neuroradiology, Hospital of Purpan and Hospital of Rangueil

- 1999–present: Professor of radiology, University of Toulouse

Education:

- 1989–1992: Fellowship in neuroradiology, Paris

- 1988–1989: Military service, CHU de Pointe-à-Pitre, Guadeloupe

- 1985–1989: Fellowship in psychiatry, Paris

- 1979–1985: Medical school, Sorbonne University

Honours (selected):

- 2012–2014: President, ESMINT

- 2009: President, inaugural ESMINT congress

- 2009: President, SFNR congress

- 2008: Invited professor, University of Montreal, Canada

- 1985: Ranked 37th among 3,500 candidates in ‘Internat des Hôpitaux de Paris’ competition