Laurent Pierot’s (Reims University Hospitals, Reims, France) long career in the treatment of intracranial aneurysms predates not only what many consider to be the advent of the interventional neuroradiology (INR) specialty, the ISAT trial, but also the introduction of the Guglielmi detachable coil (GDC) in 1990. Speaking with NeuroNews, he draws on the major shifts and trends he has observed over the past three decades to speculate on what INR’s future may hold.

“I started training with Jacques Moret a little bit before the GDCs were available, in 1985,” he recalls. “At that time, we were still treating aneurysms with a balloon—you can imagine, it was a big mess. We started the procedure at 9am and finished at around 3pm!”

But, he continues, the ISAT trial—published in The Lancet in 2002—“changed everything” by establishing the role of endovascular coiling alongside neurosurgical clipping as a viable aneurysm therapy. While this may remain the single most important moment in the relatively short history of INR, Pierot has witnessed numerous other advancements in aneurysm care over the past 20 years—even playing a direct role in many of them.

Balloons and stents have both been used as adjunctive, supporting devices during coil embolisation procedures, with Pierot and many of his colleagues in France preferring the former technique, while those in the USA and Germany are traditionally more reluctant to use balloon-assisted coiling and thus tend to gravitate towards stenting.

“What we were always missing was a study demonstrating the benefits of stenting in terms of recanalisation,” Pierot notes. “There were some subgroup analyses, yes, but what we needed was a randomised controlled trial [RCT]; and we still do not have it. For that reason, I do not use many stents, because we have no proof that it is reducing the recanalisation rate and, now, most of the time, I will use flow diverters, as their benefit is clearly established.”

Here, Pierot touches on the next key development in endovascular aneurysm treatment: the introduction of flow diversion, and devices like Pipeline (Medtronic), Silk (Balt) and Surpass (Stryker), nearly 15 years ago. He notes that, while earlier flow-diverter trials like PUFS indicated “excellent” efficacy results but at the cost of relatively high complication rates, more recent studies indicate that modern flow-diversion technologies can achieve comparable safety outcomes to coiling.

“In 10 years, the safety has dramatically improved, with a reduction in complication rates—probably due to the improvement of devices and also the skills of the physicians,” Pierot avers, before highlighting the FRED (Microvention/Terumo) and P64 (Phenox/Wallaby) flow diverters that have come to the fore more recently.

Present day

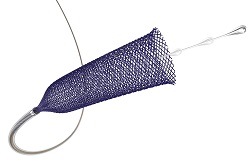

Along the timeline of INR innovation, the latest major introduction has been that of intrasaccular devices, most notably with the well-established Woven EndoBridge (WEB; Microvention/Terumo) and, more recently, the Contour (Cerus/Stryker) system in Europe. Pierot describes the arrival of the WEB device on the market as a “tremendous change” in clinical practice, and one that opened up vital new possibilities in the treatment of more challenging intracranial aneurysms.

“You have to realise that we were facing these very wide-neck bifurcation aneurysms and I remember, before WEB, I can tell you that I was not very comfortable treating these kinds of aneurysms, because it was a difficult task,” he notes. “So, WEB really changed the face of the treatment of this aneurysm subgroup.”

With coiling, flow diversion and now intrasaccular devices all constituting staple parts of an interventional neuroradiologist’s armoury, Pierot feels there is a certain equilibrium that can be seen across current technologies used to treat aneurysms.

“I am sure of one thing and, when I discuss with industry, they say the same thing: as of now, the number of coils, globally, is not increasing—except in developing countries where the evolution of endovascular aneurysm treatment is still happening,” Pierot says. “But, in the USA and Europe, the rate of coiling is more or less stable. And, in my mind, the future of aneurysm treatment is clearly flow diverters and intrasaccular devices.”

Far from the seismic shifts brought about by GDCs, the ISAT study, and the principle of flow diversion being established, Pierot believes more incremental improvements to these already available tools are on the horizon.

“For the time being, I do not see so many innovations coming onto the market,” he continues, “and I think the most important innovation we will have is surface modification of flow diverters because—if it works—maybe we will be able to use flow diverters in ruptured aneurysms.”

Ruptured versus unruptured

As things stand, the two endovascular options for the vast majority of ruptured aneurysm cases are coils and intrasaccular devices. According to Pierot, while a comparative RCT to evaluate the two against one another has never been conducted, both techniques are “very safe” and any differences between the two on this front “will not be large”. In addition, both have demonstrated their efficacy, with large-scale studies showing the WEB device can achieve “similar protection” against rebleeding as compared to coiling.

Conversely, the use of flow diversion in ruptured aneurysms is currently limited to a handful of “very specific” indications, such as ‘blister-like’ aneurysms, which are too small to be treated via coil or intrasaccular-device placement.

“But maybe what will change in the future is that we will be able to use a flow diverter with single antiplatelet therapy [SAPT] in more ruptured aneurysm cases, and during the acute bleeding phase,” Pierot says, alluding to the potential held by surface modification as a means for removing the need for patients to receive dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) following flow-diverter placement.

Flow-diverter technologies like the Pipeline Shield (Medtronic) and P64 MW with hydrophilic coating (HPC; Phenox/Wallaby) are notable examples of existing devices ‘coated’ with agents designed to reduce platelet aggregation—meaning patients can, in theory, receive SAPT rather than DAPT without an increased risk of haemorrhagic complications.

Pierot has been heavily involved in several trials that have proved key to establishing today’s INR practices, including ATENA and CLARITY— which evaluated coiling in unruptured and ruptured aneurysms, respectively—as well as the first three European studies assessing WEB. And, now, as the principal investigator for the COATING study involving the P64 MW with HPC, he is at the forefront of what he believes may be the next major leap forward in endovascular aneurysm care.

In addition to establishing the principle of surface modification, if successful, he believes COATING could be the “first step” towards opening the door for flow diversion to be deployed across a greater range of aneurysm types, with further subsequent trials being necessary to truly ascertain if surface-modified devices can be used in ruptured aneurysms.

“And, for unruptured aneurysms, it is completely clear in my mind that we no longer have to use coils— at least as the primary treatment,” Pierot goes on. “We have to use intrasaccular devices or flow diverters, and coiling is for a limited number of indications.”

He also feels that a question mark remains over the respective indications of intrasaccular devices and flow diverters in bifurcation aneurysms, noting that a comparative study may be required in this space.

“In the beginning, WEB was the most indicated device for bifurcation aneurysms, and flow diversion was criticised because it means you are obliged to cover one branch of the bifurcation, leading to its occlusion or reduction in size and potentially causing a stroke,” Pierot says, adding that, as such, he was “very reluctant” to use flow diverters in these cases. However, technological improvements and fresh studies over the past few years have led to these devices being considered a far more viable option in bifurcation aneurysms.

And, while Contour is more of a newcomer in the intrasaccular space, and is yet to be bolstered by the same evidence base behind WEB, Pierot believes more stringent evaluations of the device could be imminent following its acquisition by Stryker earlier this year. He goes on to note that available data on this device are “very limited”, and that large-scale studies will be needed to confirm its safety, as well as long-term follow-up results to evaluate efficacy. Nevertheless, Pierot does highlight a key theoretical benefit of Contour: the fact it comes in a far smaller number of sizes compared to WEB and, thus, could help to reduce the complexity of some treatment decisions.

Looking forward

Pierot chooses to divide possible future advancements in aneurysm care into two categories, with the first concerning more novel technologies like robotics, which could lead to improved precision and even remote procedures further down the line, and artificial intelligence, which has the potential to support patient selection and treatment decisions. He also notes that flat-panel computed tomography and other imaging advances made by the likes of Philips and Siemens Healthineers, have occurred alongside the expansion of INR treatments, and will continue to do so.

The second, however—the devices themselves— is where improvements will truly alter the current indications of endovascular aneurysm treatments, he feels. Pierot highlights the significant changes longstanding flow diverters like Pipeline and Surpass have undergone through the past decade, reporting from experience that newer generations of both are now easier to use as well as producing improved outcomes.

Some device innovations can be seen across much of the INR industry already; for example, Pierot notes, many companies are currently striving to reduce the sizes of their microcatheters in an effort to improve navigability and, thus, the safety of endovascular procedures. Others are more recent and carry less certainty—Pierot highlights a recent revival of interest in the use of liquid embolic agents to treat intracranial aneurysms, but admits scepticism given previous failings of Onyx (Medtronic) in this space.

“I think what we need is interaction,” Pierot concludes, speculating on what the INR community—physicians and industry alike—can do to push the field forward. “We need to have interaction with the companies, and we need to have discussions with the engineers to see what new technologies and improvements to existing technologies they can bring us. And, we have to give them our feedback to ensure the continuous improvement of these devices.”

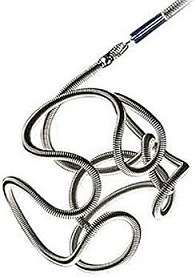

In coiling, he states that device improvements have been made over the course of the past 30 years but that, now, all shapes and sizes are available, and further significant advances are unlikely; “it is done”, Pierot comments regarding this area.

“So, what we have to work on is the continued improvement of flow diversion—for example, flow diversion with a material that will disappear after several days or weeks is something companies are working on—and of intrasaccular devices,” he states. “The main goal in aneurysm treatment is to maintain a high level of safety while improving efficacy and decreasing the rate of recanalisation.”

Closing the conversation, Pierot suggests ease of use is a key consideration regarding future devices, particularly as the INR specialty expands and draws in a greater number of young, less experienced operators.

“It is a concept I was not too supportive of at the beginning, but we now have an increasing number of physicians in the field so, for them, it is important to have a technology that is not too complicated to use,” he opines. “The ideal device would be one that is positioned at the level of the neck, blocking it, without placing anything inside the aneurysm sac, in order to stimulate endothelialisation and closure of the neck. So, the companies have to make a device like this to treat aneurysms in the future!”