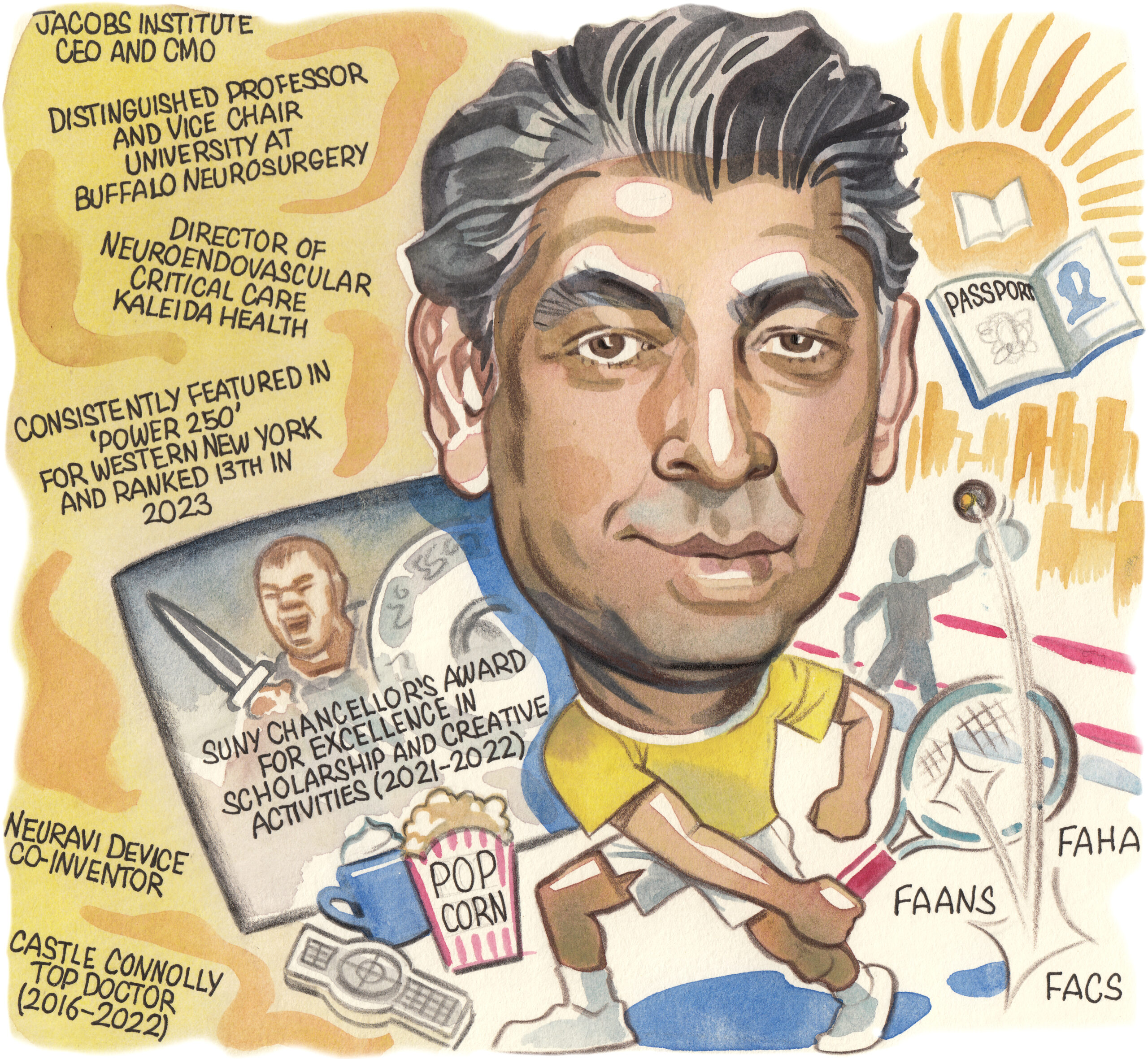

While he is a neurosurgeon by trade, Adnan Siddiqui (Buffalo, USA) has delved into an increasing number of domains throughout his career—not only through his interest in endovascular treatments and the neurosciences, but also via significant involvement in clinical trials, translational research, and even entrepreneurship. Here, the chief executive officer and chief medical officer of the Jacobs Institute, who is also a distinguished professor and vice-chairman of neurosurgery for the University at Buffalo, speaks to NeuroNews to chart his journey and provide insights on several major topics.

What initially drew you to medicine, and the field of neurointervention specifically?

My first real encounter with neurosurgery was after a car accident in Pakistan. I was on vacation with my family in the Himalayas, and our Jeep fell off a mountain. My brother died from a spinal cord injury, and my sister was severely hurt due to closed head trauma—so, I had to deal with neurosurgeons every single day and I distinctly remember feeling that they had no idea as to what the outcome was going to be. It was just this incredibly primitive field and, because of that, I wanted to become a neurosurgeon who could give different answers to the ones I had received. That was right before I started medical school in Pakistan, at Aga Khan University. I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do in medical school—I thought maybe cardiac surgery, but all I was doing as a student was holding the heart in an ice-cold bucket, freezing my hands and not having fun! I didn’t particularly like general surgery or urology. Then, one day, I saw a neurosurgeon operating on a brain arteriovenous malformation (AVM). It was my first time seeing the living human brain and I thought it was the most magnificent, beautiful thing I’d ever seen. The brain ‘beats’ at its own pace—it makes us who and what we are. So, that was a very profound experience, and I was hooked. I said: “Okay, I’m going to become a neurosurgeon”.

Who have your key mentors been and how have they impacted your career?

My first mentor was neuroscientist Shirley Joseph. I did my PhD with her at the University of Rochester. She was an anatomist by training, and I absolutely loved anatomy, but I also learned a lot about electrophysiology, molecular biology and such. Translational research has subsequently been a big part of my life, and I still run the Canon Stroke and Vascular Research Center doing entirely translational, basic science work. My neurosurgeon mentor was Charlie Hodge. He was neurosurgery chair at Upstate Medical University in Syracuse. He did complicated skull-base and vascular surgery, and he really inspired me in terms of the practises that I have on the cranial and open neurosurgical side. On the endovascular side, it’s somebody I later joined rather than trained with: Nick Hopkins. It’s not so much that I learnt particular techniques with him—it was that mindset, where you bring all the forces to bear. You bring your education, research background, cranial skills, and endovascular skills, to instigate change through innovation, through discovery, through entrepreneurship. Having all those facets, all at the same time, is all Nick Hopkins. I would say, of all my mentors, he’s the one that I’m most indebted to in terms of who I am now.

The Jacobs Institute has become something of a centre of excellence for medical research in recent years—how have you and your colleagues achieved this?

The incredible imagination of Nick Hopkins led to this concept. At a time when many people were focused on neuroscience institutes, he thought we needed vascular institutes where cardiologists, interventional (neuro)radiologists, vascular surgeons, cardiac surgeons and neurosurgeons could pool their resources and experiences. That’s how the Gates Vascular Institute in Buffalo was born and, then—again, Nick’s genius—he convinced the university to build the Clinical and Translational Research Center, dedicated to neuro and vascular translational research, above the hospital. He also wanted to create a partnership-focused centre that could utilise hospital and university resources to optimise the field through entrepreneurship. That’s the genesis of the Jacobs Institute. Today, our goal is to create new medical devices that improve outcomes for patients who have neurologic or vascular diseases, and we’ve done a variety of things to help us achieve this. Early on, we created training programmes, leveraging incredible physicians like Elad Levy (neurosurgery), Vijay Iyer and David Zlotnick (cardiology), Sonya Noor (vascular surgery), and many others. We’ve developed a high level of competency training advanced practitioners—not just physicians, but also engineers, industry and regulators—on how particular disease states can be managed. Now led by Pam Marcucci, that’s been incredibly successful. We also gained an interest in advanced 3D-printed models of the brain to simulate the human anatomy, as well as good laboratory practice (GLP) animal studies, early feasibility studies (EFS) and other ways to test devices to support regulatory approval. We currently have eight first-in-human studies going on here in Buffalo. When Carlos Peña joined us from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), that was a godsend too, as he’s built an extremely robust regulatory services programme for companies aspiring to get their devices approved in the USA. The last part, we call ‘idea to reality’ (i2R), where someone comes to us with a concept, and we develop and prototype it for an equity share. That’s been quite a recent development but, now, we can essentially make any device for vascular or neurosurgical applications. So, you can see there’s an ecosystem that has evolved and, hopefully, it won’t be long before we have a successful exit for one or more of the startups in our i2R Center.

Of all the clinical studies you’ve been involved with, which do you think has had the greatest impact?

From close to 800 publications, a few really stand out. The earliest one is PREMiSe, which was my first true clinical trial. It assessed venous angioplasty—via the ‘liberation’ procedure—in multiple sclerosis (MS) patients. I learned the technique and did a double-blinded, sham-controlled, randomised trial, which demonstrated that, not only did the procedure not help, but it actually caused harm. So, that trial was negative but also incredibly impactful, because we helped prevent a lot of people with MS from undergoing unnecessary surgery. I’m also very proud of my participation in the PUFS trial that led to the approval of the Pipeline (Medtronic) device, as I think flow diversion has been absolutely transformational for aneurysm therapies. I was really frustrated with the 2013 stroke thrombectomy trials, but we were anticipating they may not be successful, and I worked with Jeff Saver and Mark Turco to design the SWIFT-PRIME trial alongside Elad Levy—he was national principal investigator (PI) and I remained on the steering committee. And, we all know how important that study was in proving that mechanical thrombectomy was the right thing to do in stroke and helping to open up the entire thrombectomy space. The most recent ones that I’m really proud of are the ENRICH trial, which has finally proven the benefits of minimally invasive clot removal in intracranial haemorrhage—and in which I was an active participant—and the EMBOLISE trial demonstrating middle meningeal artery embolisation as a potential treatment option in chronic subdural haematoma, which I developed alongside national PIs Jason Davies and Jared Knopman.

How do you envisage the neuroendovascular space evolving in the future?

We are at the very beginning of switching from our roles as ‘plumbers’ to people who actually interact with and manipulate the brain. Endovascularly, we’ve essentially been focusing on things that are ruptured or blocked, but I think brain-machine interface, brain neurophysiology and structural diseases are going to be the next transformational stage. Adel Malek and Carl Heilman’s idea of putting a tiny tube through the inferior petrosal sinus, into the cerebellopontine angle, to drain cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and treat communicating hydrocephalus is absolutely brilliant, and there’s no question in my mind that it’s a gateway technology for others to use this transvascular route to do things in the brain. That could be to drain CSF, like Cerevasc, or to place devices inside—for example, to avoid doing a craniotomy entirely when implanting a brain-machine interface, like Synchron. So, just as cardiology was revolutionised by electrophysiology and structural heart, I think that’s coming to the neuro space now.

Which research areas are likely to have the greatest impact on neurointerventional surgery over the next 10 years?

I’m currently focusing a lot of what I do at the Canon Stroke and Vascular Research Center on endovascular treatments for glioblastoma multiforme, and using the vascular route to deliver chemotherapy to maintain, shrink or even cure the tumour. We’ve begun a line of research testing this in rats to see which agents work and I think that’s going to be an incredible opportunity for neuro-oncology—it’s probably a few years away, but it’s coming. I’m also really fascinated by the work of Maiken Nedergaard, who discovered the glymphatic system, and showed that CSF is absolutely critical in every aspect of brain functionality. We now have the ability to potentially manipulate these ‘glymphatics’ to improve outcomes for disorders not considered at all neurosurgical; degenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and cognitive dementias, or normal-pressure hydrocephalus. These are all just hypotheses and, again, currently at the animal-testing stage, but I think that’s going to be a whole new area and I’m really excited about it.

What are your interests outside of medicine?

I love playing squash with my sons and hoping they go easy on me! I enjoy travelling to new places, and I’m fortunate that I’m invited all over the world and can gain that experience. I love watching good movies—Gladiator is probably my favourite—and the only type I don’t enjoy is horror. Finally, I must admit I’m addicted to binge-watching a good TV series at night.

What’s your favourite place you’ve visited?

I have a strong bias towards Jackson Hole; it’s one of my favourite places on the planet. When I go there, it just lowers my heartrate by 10–15 beats and, someday, I’d like to have a place there.

If you had not opted for a career in medicine, what do you think you would be doing for a living today?

When I applied, I promised myself that—if I did not match in a neurosurgical programme the very first time—I was going to quit medicine and science entirely, and go into foreign affairs, and some kind of international peacekeeping profession. As a neurosurgeon, I’ve done 20,000 or so cases, and hopefully helped most of those patients, but the impact diplomats and peacekeepers can have is logarithmically even greater. I’ve always been fascinated by that area and, maybe, if I have enough life in me after neurosurgery, I might still do something like that.

FACT FILE

Current appointments:

- Chief executive officer and chief medical officer, Jacobs Institute (Buffalo, USA)

- Distinguished professor and vice-chairman of Neurosurgery, University at Buffalo

- Director, Canon Stroke and Vascular Research Center

- Director of Neuroendovascular Critical Care and Neurosurgical Stroke Service, Kaleida Health

Education:

- 1992: MBBS, Medicine/Surgery (Aga Khan University Medical College, Karachi, Pakistan)

- 2003: PhD, Neuroscience (University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, USA)

- 1999–2004: Resident, Neurosurgery (State University of New York [SUNY] Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, USA)

- 2005–2006: Fellow, Cerebrovascular Surgery, Interventional Neuroradiology and Neurocritical Care (Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, USA)

Honours (selected):

- 2004: Arnold P Gold Foundation National Award for Humanism and Excellence in Teaching

- 2012: George Thorn Young Investigator Award, Jacobs School

- 2017: Inaugural recipient of Ahuja Endowed Clinical Professorship of Cerebrovascular Surgery

- 2021–2022: SUNY Chancellor’s Award for Excellence in Scholarship and Creative Activities

- 2023: Ranked 13th on Power 250 Buffalo’s Business Leaders, Buffalo Business First