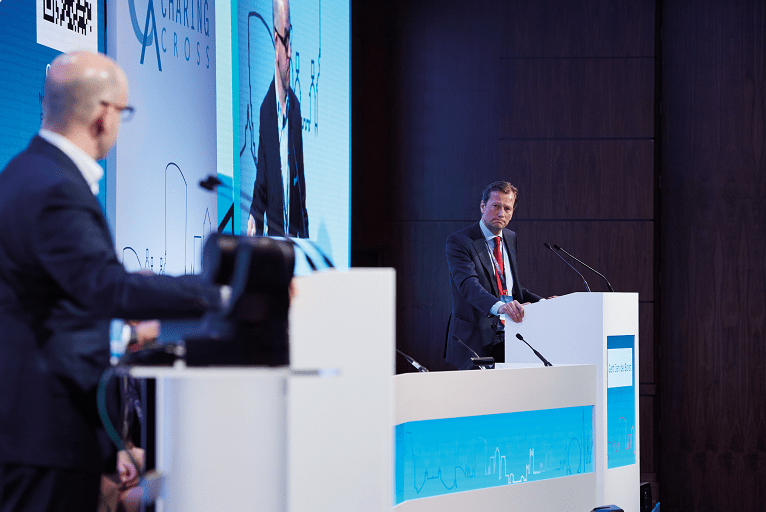

Audience polling during the Acute Stroke Challenges session at this year’s Charing Cross Symposium (CX 2022; 26–28 April, London, UK and virtual) revealed scepticism regarding the benefits of transcarotid artery revascularisation (TCAR) in the treatment of symptomatic carotid artery stenosis. This followed a debate that saw Michael Stoner (University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, USA) and Gert J de Borst (University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands) go head-to-head over the quality of evidence supporting TCAR as compared to carotid endarterectomy (CEA) and carotid artery stenting (CAS).

Stoner presented first, arguing in favour of the motion that “TCAR is a safe and effective alternative to transfemoral CAS or CEA in the treatment of patients with symptomatic internal carotid artery stenosis”. He noted that one of the “theoretical advantages” of TCAR is distal embolic neuroprotection—something he feels has been demonstrated in the PROOF and DW-MRI-US studies, while the multicentre ROADSTER and ROADSTER 2 trials, and the Vascular Quality Initiative (VQI) registry, have all shown low 30-day stroke rates among symptomatic patients.

The speaker claimed that the ipsilateral stroke rates seen between 31 and 365 days in ROADSTER and ROADSTER 2 (0.6% and 0%, respectively) show long-term efficacy with TCAR, and other small case series from the USA have corroborated this. Examining data from the VQI registry further, Stoner highlighted findings published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, which include 3,658 symptomatic patients, and reveal a 2.6% rate of stroke or death at 30 days in patients treated with TCAR compared to 4.8% in patients treated via CAS. Pivoting to a propensity score-matched analysis from the same dataset, Stoner noted “matched” 30-day stroke/death rates between TCAR and CEA, as well as “improved” 30-day stroke/death rates with TCAR compared to CAS.

He concluded his argument in favour of the motion by stating that prospective case and case-control studies demonstrate safety and efficacy with TCAR, as well as early advantages over CAS and statistically insignificant differences versus CEA, in patients with appropriate anatomies (symptomatic and high-risk asymptomatic carotid stenoses). “We recommend maintaining guideline-based revascularisation with regard to timing,” Stoner added, but conceded that randomised controlled trial (RCT) data are currently unavailable.

The riposte to this was then provided by de Borst, who began by addressing the “elephant in the room” his opponent had already alluded to—the current lack of RCTs directly comparing TCAR to CEA or CAS. In addition, he noted that the vast majority of the datasets presented by Stoner were dominated by asymptomatic patients. Highlighting further concerns with the existing body of evidence on TCAR, de Borst claimed it is mostly derived from company-sponsored, single-arm studies, while three quarters of all the included patients originate from the VQI registry—limiting generalisability—and there is an underreporting of anatomic suitability and exclusion criteria too.

The riposte to this was then provided by de Borst, who began by addressing the “elephant in the room” his opponent had already alluded to—the current lack of RCTs directly comparing TCAR to CEA or CAS. In addition, he noted that the vast majority of the datasets presented by Stoner were dominated by asymptomatic patients. Highlighting further concerns with the existing body of evidence on TCAR, de Borst claimed it is mostly derived from company-sponsored, single-arm studies, while three quarters of all the included patients originate from the VQI registry—limiting generalisability—and there is an underreporting of anatomic suitability and exclusion criteria too.

De Borst touched on further shortcomings of the current TCAR literature, focusing in particular on the fact that, despite the procedure being developed to prevent embolic complications, evidence supporting its efficacy here is “very modest”, with no high-quality studies available as things stand. “We have clear data on the efficacy and safety of surgery [CEA] in symptomatic patients, and we also know that stroke risks and the rate of new DW-MRI [diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging] lesions are higher in transfemoral stenting, but we do not have any data on these aspects in TCAR,” he added.

His concluding message was that, while CAS has “evolved considerably” over the past two decades, CEA remains the safer option of the two for the majority of patients, and across all periods after the onset of symptoms. De Borst also noted that current evidence may seem “promising”, but independent, investigator-driven studies comparing TCAR to CEA in recently symptomatic patients are needed to establish its true value.

In the discussion after this debate, a show of hands from the audience revealed that very few of the hundreds in attendance had performed TCAR before, with Stoner suggesting this is consistent with the procedure’s more limited European availability. And, upon being quizzed on the possible reasons why uptake of TCAR is still relatively low in the USA compared to other carotid artery stenosis treatments as well, he said this is likely a result of logistical barriers, such as all asymptomatic patients needing to be treated within the VQI registry, and also economic factors, including Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) reimbursement issues and the fact that—at least in the short-term—CEA is the far cheaper option.

When pressed by Stoner on data that may “change his tune” regarding TCAR, de Borst said that RCTs, or at least prospective, high-quality registry evidence involving patients selected on the same criteria, are required. “That basis is lacking,” he continued. “There are some pros and some cons, but I think the strong points of TCAR could easily be evaluated in a prospective setup. Really, the question is: Why don’t we do it?”. Following Stoner’s admission that there are “undeniable selection biases” within much of the existing data, the majority of the CX audience was ultimately swayed by de Borst’s arguments, with 79% voting against the motion.